Why Days of Supply Targets Don’t Work when Computing Safety Stocks

CFOs tell us they need to spend less on inventory without impacting sales. One way to do that is to move away from using targeted day of supply to determine reorder points and safety stock buffers. Here is how a days of supply model works:

- Compute average demand per day and multiply the demand per day by supplier lead time in days to get lead time demand

- Pick a days of supply buffer (i.e., 15, 30, 45 days, etc.). Use larger buffers being used for more important items and smaller buffers for less important items.

- Add the desired days of supply buffer to demand over the lead time to get the reorder point. Order more when on hand inventory falls below the reorder point

Here is what is wrong with this approach:

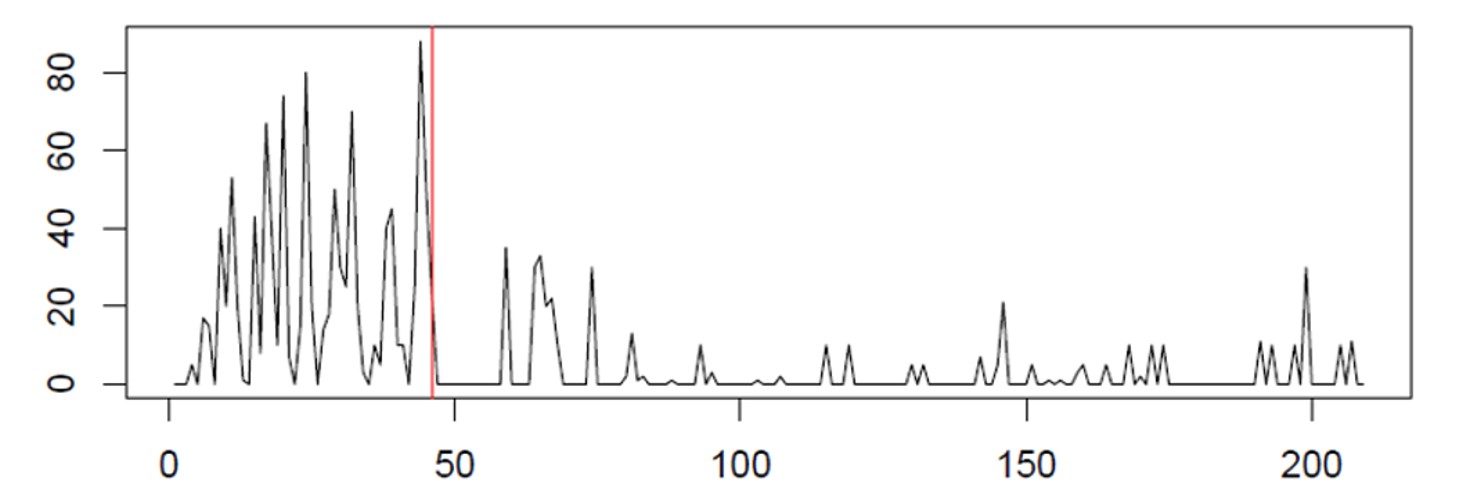

- The average doesn’t account for seasonality and trend – you’ll miss obvious patterns unless you spend lots of time manually adjusting for it.

- The average doesn’t consider how predictable an item is – you’ll overstock predictable items and understock less predictable ones. This is because the same days of supply for different items yields a very different stock out risk.

- The average doesn’t tell a planner how stock out risk is impacted by the level of inventory – you’ll have no idea whether you are understocked, overstocked, or have just enough. You are essentially planning with blinders on.

There are many other “rule of thumb” approaches that are equally problematic. You can learn more about them in this post.

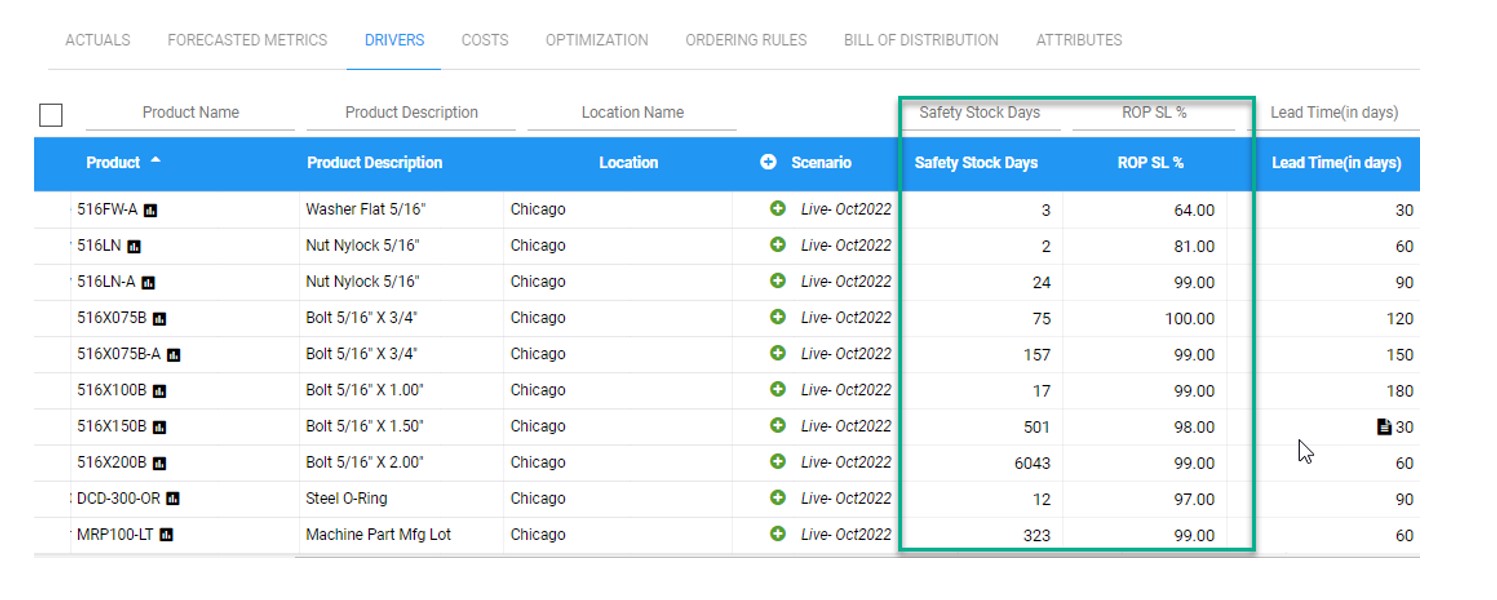

A better way to plan the right amount of safety stock is to leverage probability models that identify exactly how much stock is needed given the risk of stock-out you are willing to accept. Below is a screenshot of Smart Inventory Optimization that does exactly that. First, it details the predicted service levels (probability of not stocking out) associated with the current days of supply logic. The planner can now see the parts where predicted service level is too low or too costly. They can then make immediate corrections by targeting the desired service levels and level of inventory investment. Without this information, a planner isn’t going to know whether the targeted days of safety stock is too much, too little, or just right resulting in overstocks and shortages that cost market share and revenue.