A forecast is a prediction about the value of a time series variable at some time in the future. For instance, one might want to estimate next month’s sales or demand for a product item. A time series is a sequence of numbers recorded at equally spaced time intervals; for example, unit sales recorded every month.

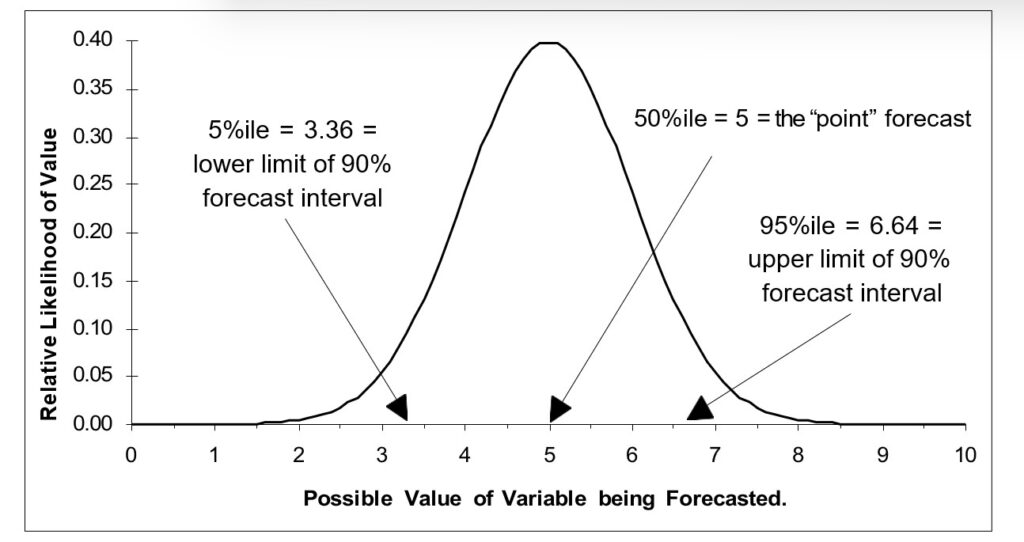

The objectives you pursue when you forecast depend on the nature of your job and your business. Every forecast is uncertain; in fact, there is a range of possible values for any variable you forecast. Values near the middle of this range have a higher likelihood of actually occurring, while values at the extremes of the range are less likely to occur. The following figure illustrates a typical distribution of forecast values.

Point forecasts

The most common use of forecasts is to estimate a sequence of numbers representing the most likely future values of the variable of interest. For instance, suppose you are developing a sales and marketing plan for your company. You may need to fill in 12 cells in a financial spreadsheet with estimates of your company’s total revenues over the next 12 months. Such estimates are called point forecasts because you want a single number (data point) for each forecast period. Smart Demand Planner’ Automatic forecasting feature provides you with these point forecasts automatically.

Interval forecasts

Although point forecasts are convenient, you will often benefit more from interval forecasts. Interval forecasts show the most likely range (interval) of values that might arise in the future. These are usually more useful than point forecasts because they convey the amount of uncertainty or risk involved in a forecast. The forecast interval percentage can be specified in the various forecasting dialog boxes in the Demand Planning Software. Each of the many forecasting methods (automatic, moving average, exponential smoothing and so on) available in Smart Demand Planner allow you to set a forecast interval.

The default configuration in Smart Demand Planner provides 90% forecast intervals. Interpret these intervals as the range within which the actual values will fall 90% of the time. If the intervals are wide, then there is a great deal of uncertainty associated with the point forecasts. If the intervals are narrow, you can be more confident. If you are performing a planning function and want best case and worst case values for the variables of interest at several times in the future, you can use the upper and lower limits of the forecast intervals for that purpose, with the single point estimate providing the most likely value. In the previous figure, the 90% forecast interval extends from 3.36 to 6.64.

Upper percentiles

In inventory control, your goal may be to make good estimates of a high percentile of the demand for a product item. These estimates help you cope with the tradeoff between, on the one hand, minimizing the costs of holding and ordering stock, and, on the other hand, minimizing the number of lost or back-ordered sales due to a stock out. For this reason, you may wish to know the 99th percentile or service level of demand, since the chance of exceeding that level is only 1%.

When forecasting individual variables with features like Automatic forecasting, note that the upper limit of a 90% forecast interval represents the 95th percentile of the predicted distribution of the demand for that variable. (Subtracting the 5th percentile from the 95th percentile leaves an interval containing 95%-5% = 90% of the possible values.) This means you can estimate upper percentiles by changing the value of the forecast interval. In the figure, “Illustrating a forecast distribution”, the 95th percentile is 6.64.

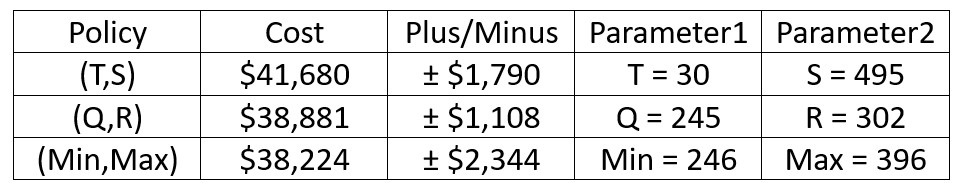

To optimize stocking policies at the desired service level or to let the system recommend which stocking policy and service level generates the best return, consider using Smart Inventory Optimization. It is designed to support what-if scenarios that show predicted tradeoffs of varying inventory polices including different service level targets.

Lower percentiles

Sometimes you may be concerned with the lower end of the predicted distribution for a variable. Such cases often arise in financial applications, where a low percentile of a revenue estimate represents a contingency requiring financial reserves. You can use Smart Demand Planner in this case in a way analogous to the case of forecasting upper percentiles. In the figure, “Illustrating a forecast distribution” , the 5th percentile is 3.36.

In conclusion, forecasting involves predicting future values, with point forecasts offering single estimates and interval forecasts providing likely value ranges. Smart Demand Planner automates point forecasts and allows users to set intervals, aiding in uncertainty assessment. For inventory control, the tool facilitates understanding upper (e.g., 99th percentile) and lower (e.g., 5th percentile) percentiles. To optimize stocking policies and service levels, Smart Inventory Optimization supports what-if scenarios, ensuring effective decision-making on how much to stock given the risk of stock out you are willing to accept.