You may remember the story of Goldilocks from your long-ago youth. Sometimes the porridge was too hot, sometimes it was too cold, but just once it was just right. Now that we are adults, we can translate that fairy tale into a professional principle for inventory planning: There can be too little or too much inventory, and there is some Goldilocks level that is “just right.” This blog is about finding that sweet spot.

To illustrate our supply chain fable, consider this example. Imagine that you sell service parts to keep your customers systems up and running. You offer a particular service part that costs you $100 to make but sells for a 20% markup. You can make $20 on each unit you sell, but you don’t get to keep the whole $20 because of the inventory operating costs you bear to be able to sell the part. There are holding costs to keep the part in good repair while in stock and ordering costs to replenish units you sell. Finally, sometimes you lose revenue from lost sales due to stockouts.

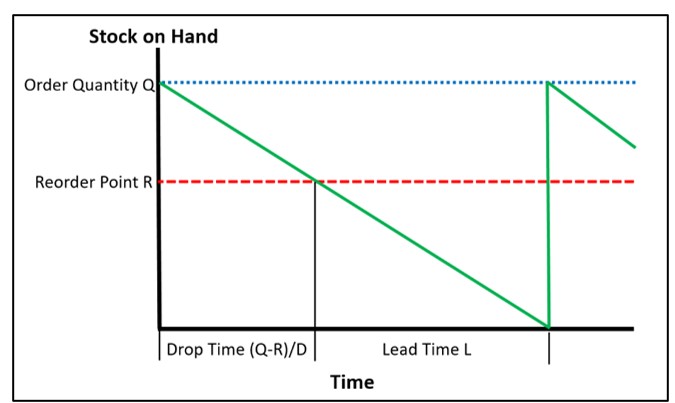

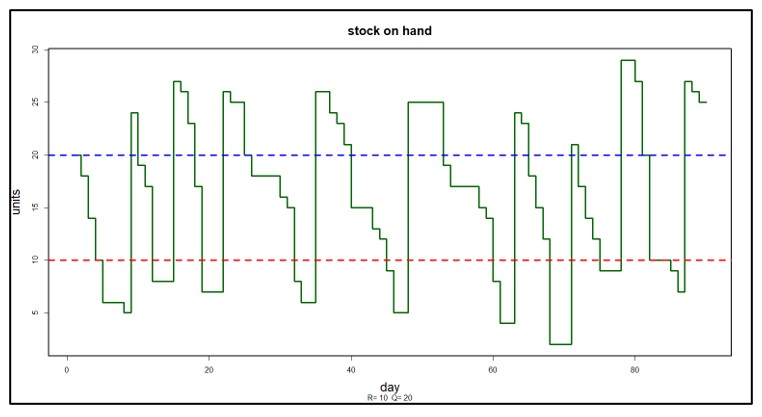

These operating costs can be directly related to the way you manage the part in inventory. For our example, assume you use a (Q,R) inventory policy, where Q is the replenishment order quantity and R is the reorder point. Assume further that the reason you are not making $30 per unit is that you have competitors, and customers will get the part from them if they can’t get it from you.

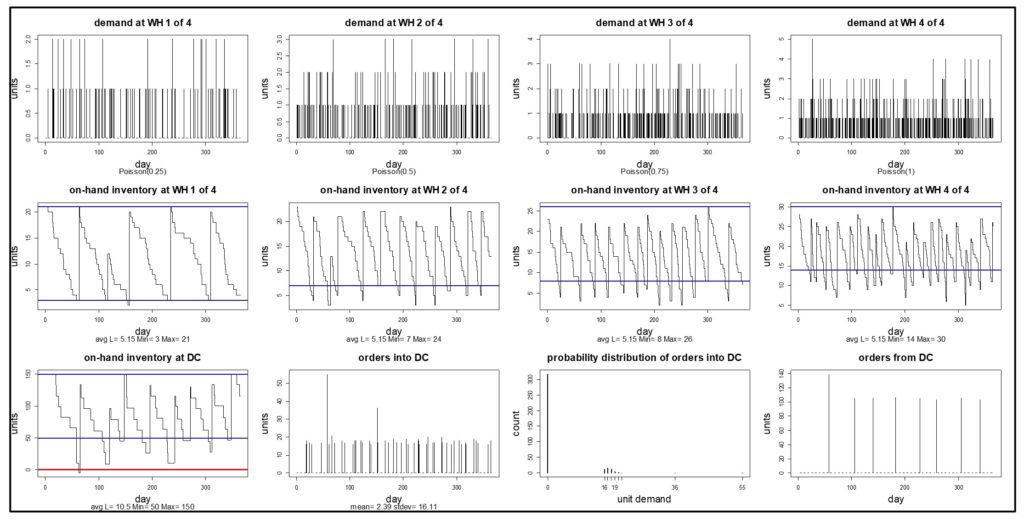

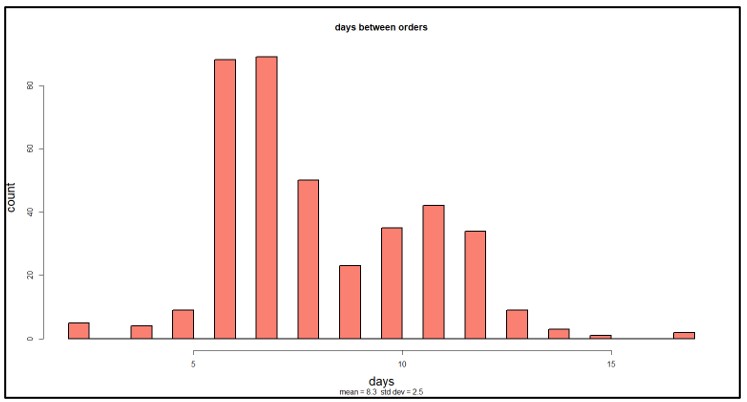

Both your revenue and your costs depend in complex ways on your choices for Q and R. These will determine how much you order, when and therefore how often you order, how often you stock out and therefore how many sales you lose, and how much cash you tie up in inventory. It is impossible to cost out these relationships by guesswork, but modern software can make the relationships visible and calculate the dollar figures you need to guide your choice of values for Q and R. It does this by running detailed, fact-based, probabilistic simulations that predict costs and performance by averaging over a large number of realistic demand scenarios.

With these results in hand, you can work out the margin associated with (Q,R) values using the simple formula

Margin = (Demand – Lost Sales) x Profit per unit sold – Ordering Costs – Holding Costs.

In this formula, Lost Sales, Ordering Costs and Holding Costs are dependent on reorder point R and order quantity Q.

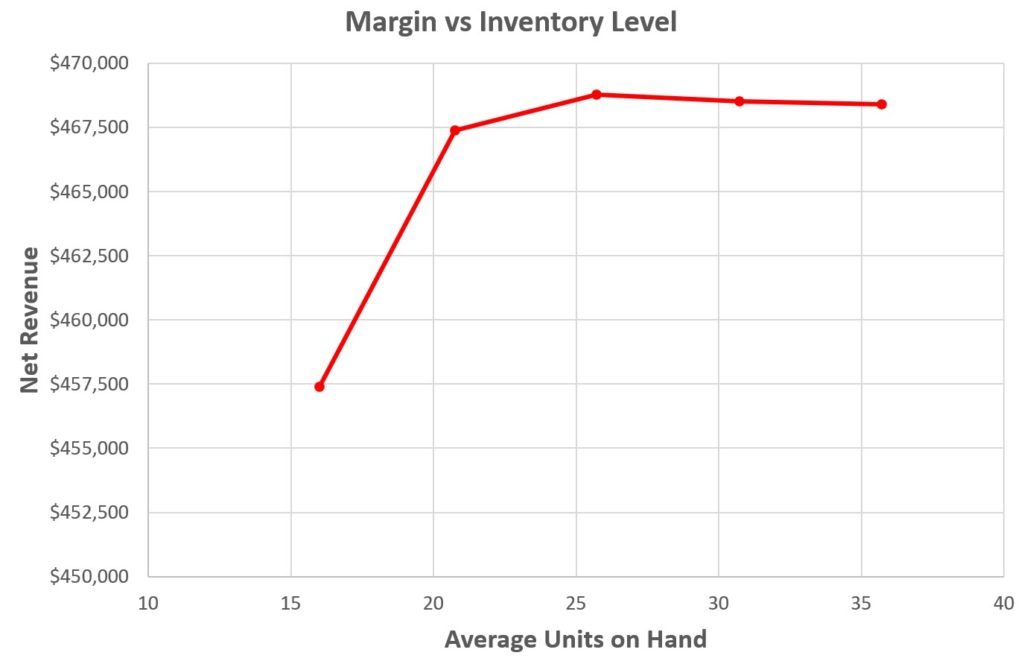

Figure 1 shows the result of simulations that fixed Q at 25 units and varied R from 10 to 30 in steps of 5. While the curve is rather flat on top, you would make the most money by keeping on-hand inventory around 25 units (which corresponds to setting R = 20). More inventory, despite a higher service level and fewer lost sales, would make a little less money (and ties up a lot more cash), and less inventory would make a lot less.

Without relying on the inventory simulation software, we would not be able to discover

- a) that it is possible to carry too little and too much inventory

- b) what the best level of inventory is

- c) how to get there by proper choices of reorder point R and order quantity Q.

Without an explicit understanding of the above, companies will make daily inventory decisions relying on gut feel and averaging based rule of thumb methods. The tradeoffs described here are not exposed and the resulting mix of inventory yields a far lower return forfeiting hundreds of thousands to millions per year in lost profits. So be like Goldilocks. With the right systems and software tools, you too can get it just right!

The Next Frontier in Supply Chain Analytics

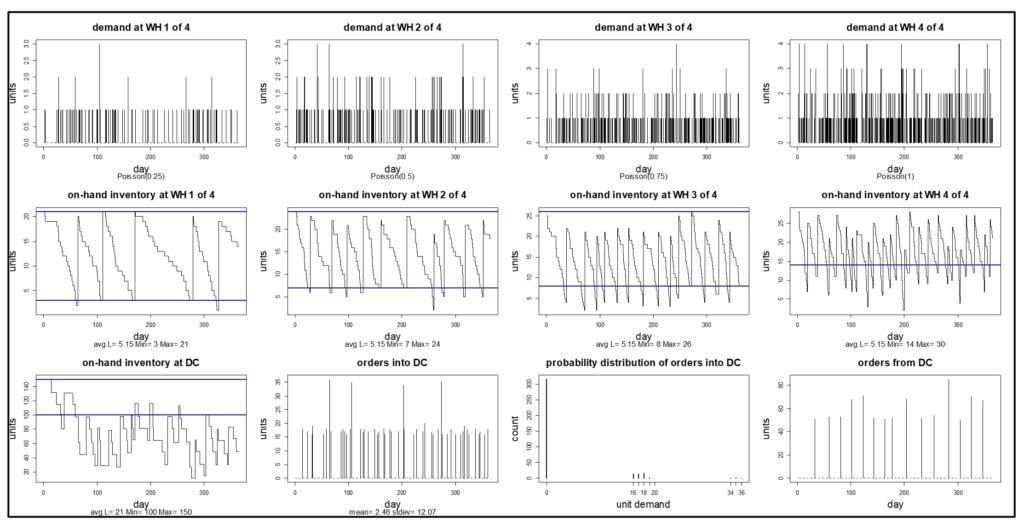

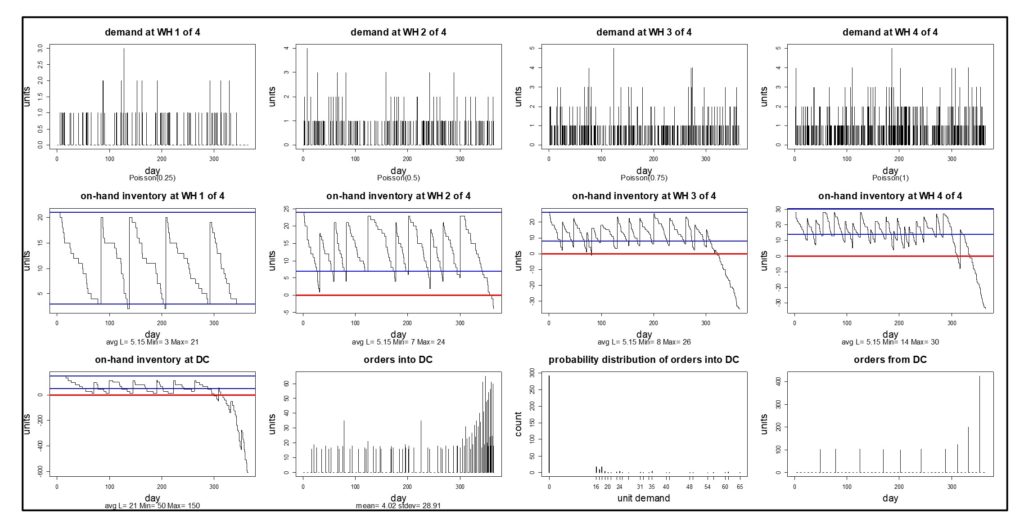

We believe the leading edge of supply chain analytics to be the development of digital twins of inventory systems. These twins take the form of discrete event models that use Monte Carlo simulation to generate and optimize over the full range of operational risks. We also assert that we and our colleagues at Smart Software have played an outsized role in forging that leading edge.

Overcoming Uncertainty with Service and Inventory Optimization Technology

In this blog, we will discuss today’s fast-paced and unpredictable market and the constant challenges businesses face in managing their inventory and service levels efficiently. The main subject of this discussion, rooted in the concept of “Probabilistic Inventory Optimization,” focuses on how modern technology can be leveraged to achieve optimal service and inventory targets amidst uncertainty. This approach not only addresses traditional inventory management issues but also offers a strategic edge in navigating the complexities of demand fluctuations and supply chain disruptions.

Centering Act: Spare Parts Timing, Pricing, and Reliability

In this article, we’ll walk you through the process of crafting a spare parts inventory plan that prioritizes availability metrics such as service levels and fill rates while ensuring cost efficiency. We’ll focus on an approach to inventory planning called Service Level-Driven Inventory Optimization. Next, we’ll discuss how to determine what parts you should include in your inventory and those that might not be necessary. Lastly, we’ll explore ways to enhance your service-level-driven inventory plan consistently.