Many companies looking to improve their forecasting process don’t know where to start. It can be confusing to contend with learning new statistical methods, making sure data is properly structured and updated, agreeing on who “owns” the forecast, defining what ownership means, and measuring accuracy. Having seen this over forty-plus years of practice, we wrote this blog to outline the core focus and to encourage you to keep it simple early on.

1. Objectivity. First, understand and communicate that the Demand Planning and Forecasting process is an exercise in objectivity. The focus is on getting inputs from various sources (stakeholders, customers, functional managers, databases, suppliers, etc.) and deciding whether those inputs add value. For example, if you override a statistical forecast and add 20% to the projection, you should not just assume that you automatically got it right. Instead, be objective and check whether that override increased or decreased forecast accuracy. If you find that your overrides made things worse, you’ve gained something: This informs the process and you know to better scrutinize override decisions in the future.

2. Teamwork. Recognize that forecasting and demand planning are team sports. Agree on who will captain the team. The captain is responsible for creating the baseline statistical forecasts and supervising the demand planning process. But results depend on everyone on the team making positive contributions, providing data, suggesting alternative methodologies, questioning assumptions, and executing recommended actions. The final results are owned by the company and every single stakeholder.

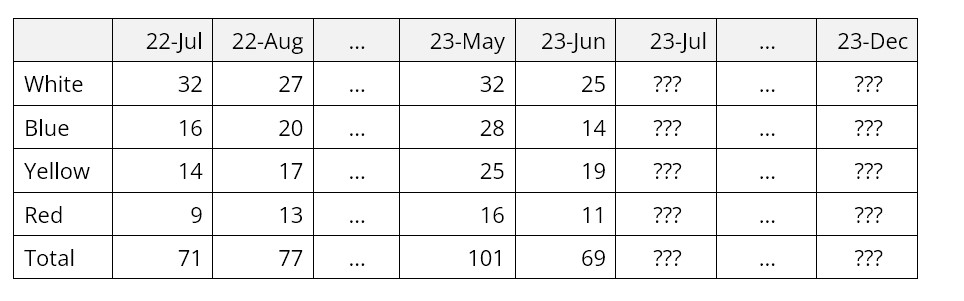

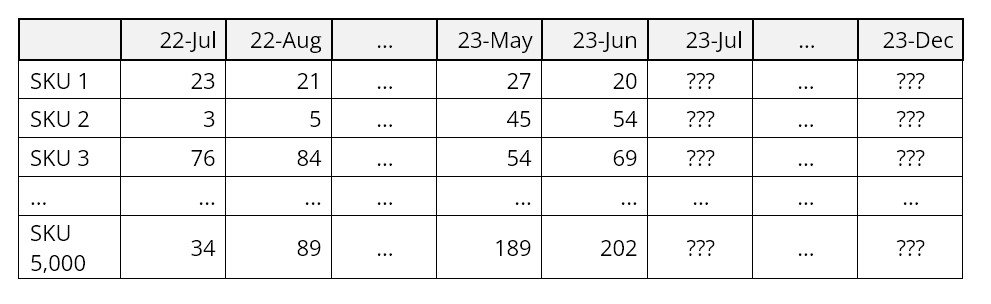

3. Measurement. Don’t fixate on industry forecast accuracy benchmarks. Every SKU has its own level of “forecastability”, and you may be managing any number of difficult items. Instead, create your own benchmarks based on a sequence of increasingly advanced forecasting methods. Advanced statistical forecasts may seem dauntingly complex at first, so start simple with a basic method, such as forecasting the historical average demand. Then measure how close that simple forecast comes to the actual observed demand. Work up from there to techniques that deal with complications like trend and seasonality. Measure progress using accuracy metrics calculated by your software, such as the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE). This will allow your company to get a little bit better each forecast cycle.

4. Tempo. Then focus efforts on making forecasting a standalone process that isn’t combined with the complex process of inventory optimization. Inventory management is built on a foundation of sound demand forecasting, but it is focused on other topics: what to purchase, when to purchase, minimum order quantities, safety stocks, inventory levels, supplier lead times, etc. Let inventory management go to later. First build up “forecasting muscle” by creating, reviewing, and evolving the forecasting process to have a regular cadence. When your process is sufficiently matured, catch up with the increasing speed of business by increasing the tempo of your forecasting process to at least a monthly cadence.

Remarks

Revising a company’s forecasting process can be a major step. Sometimes it happens when there is executive turnover, sometimes when there is a new ERP system, sometimes when there is new forecasting software. Whatever the precipitating event, this change is an opportunity to rethink and refine whatever process you had before. But trying to eat the whole elephant in one go is a mistake. In this blog, we’ve outlined some discrete steps you can take to make for a successful evolution to a better forecasting process.