Do MRO companies genuinely prioritize reducing excess spare parts inventory? From an organizational standpoint, our experience suggests not necessarily. Boardroom discussions typically revolve around expanding fleets, acquiring new customers, meeting service level agreements (SLAs), modernizing infrastructure, and maximizing uptime. In industries where assets supported by spare parts cost hundreds of millions or generate significant revenue (e.g., mining or oil & gas), the value of the inventory just doesn’t raise any eyebrows, and organizations tend to overlook massive amounts of excessive inventory.

Consider a public transit agency. In most major cities, the annual operating budgets will exceed $3 billion. Capital expenses for trains, subway cars, and infrastructure may reach hundreds of millions annually. Consequently, a spare parts inventory valued at $150 million might not grab the attention of the CFO or general manager, as it represents a small percentage of the balance sheet. Moreover, in MRO-based industries, many parts need to support equipment fleets for a decade or more, making additional stock a necessary asset. In some sectors like utilities, holding extra stock can even be incentivized to ensure that equipment is kept in a state of good repair.

We have seen concerns about excess stock arise when warehouse space is limited. I recall, early in my career, witnessing a public transit agency’s rail yard filled with rusted axles valued at over $100,000 each. I was told the axles were forced to be exposed to the elements due to insufficient warehouse space. The opportunity cost associated with the space consumed by extra stock becomes a consideration when warehouse capacity is exhausted. The primary consideration that trumps all other decisions is how the stock ensures high service levels for internal and external customers. Inventory planners worry far more about blowback from stockouts than they do from overbuying. When a missing part leads to an SLA breach or downed production line, resulting in millions in penalties and unrecoverable production output, it is understandable.

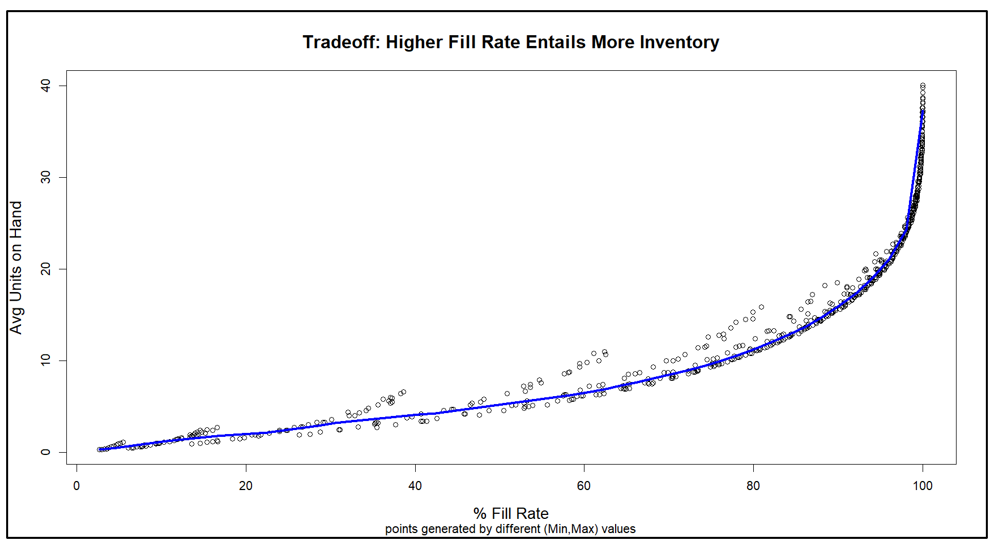

Asset-intensive companies are missing one giant point. That is, the extra stock doesn’t insulate against stockouts; it contributes to them. The more excess you have, the lower your overall service level because the cash needed to purchase parts is finite, and cash spent on excess stock means there isn’t cash available for the parts that need it. Even publicly funded MRO businesses, like utilities and transit agencies, acknowledge the need to optimize spending, now more than ever. As one materials manager shared, “We can no longer fix problems with bags of cash from Washington.” So, they must do more with less, ensuring optimal allocation across the tens of thousands of parts they manage.

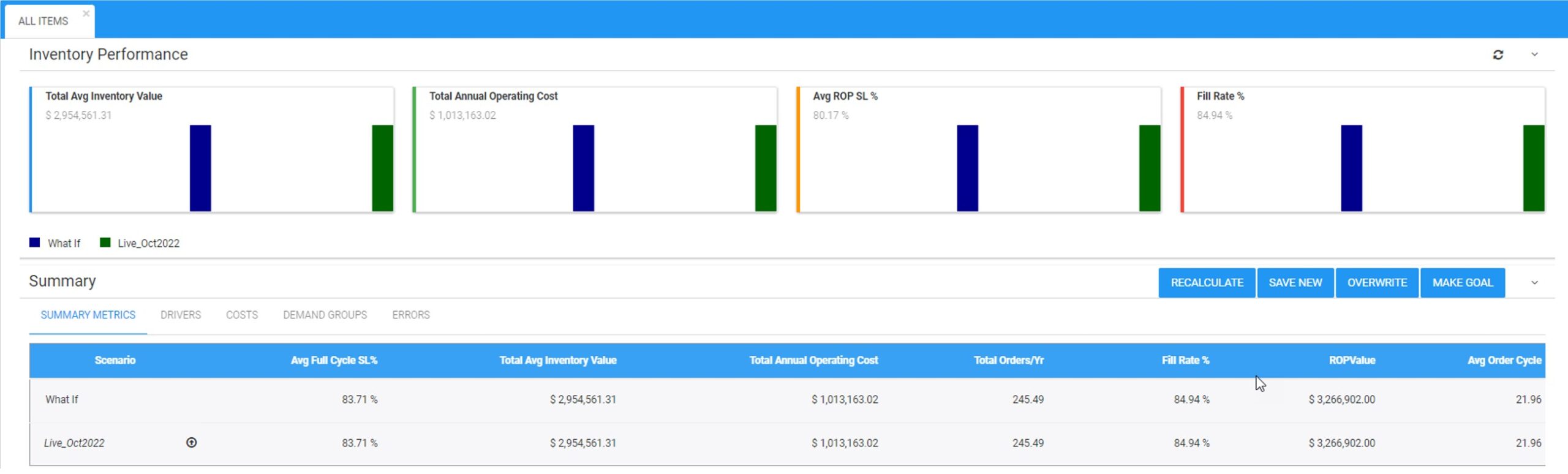

This is where state-of-the-art inventory optimization software comes in, predicting the required inventory for targeted service levels, identifying when stock levels yield negative returns, and recommending reallocations for improved overall service levels. Smart Software has helped asset intensive MRO based businesses optimize reorder levels across each part for decades. Give us a call to learn more.

Spare Parts Planning Software solutions

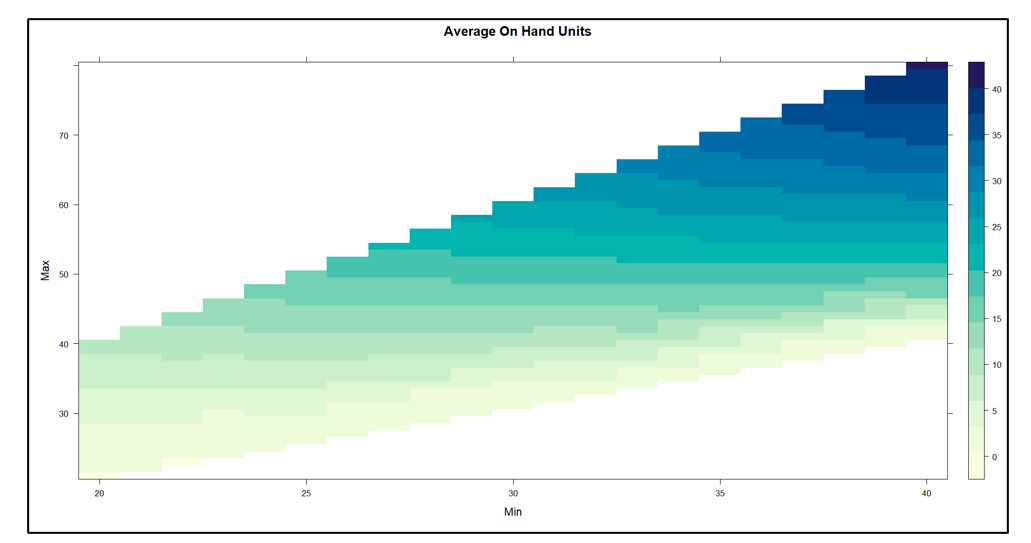

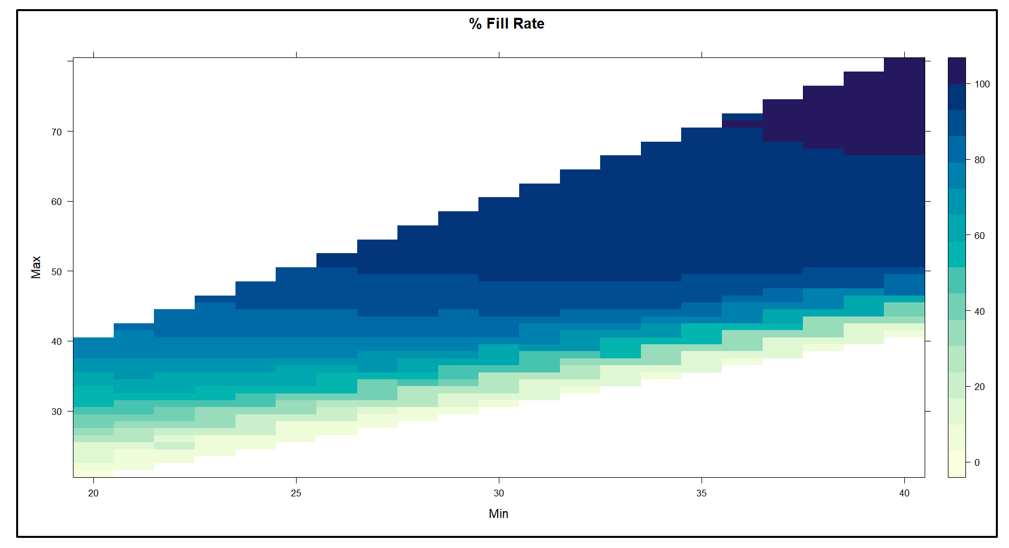

Smart IP&O’s service parts forecasting software uses a unique empirical probabilistic forecasting approach that is engineered for intermittent demand. For consumable spare parts, our patented and APICS award winning method rapidly generates tens of thousands of demand scenarios without relying on the assumptions about the nature of demand distributions implicit in traditional forecasting methods. The result is highly accurate estimates of safety stock, reorder points, and service levels, which leads to higher service levels and lower inventory costs. For repairable spare parts, Smart’s Repair and Return Module accurately simulates the processes of part breakdown and repair. It predicts downtime, service levels, and inventory costs associated with the current rotating spare parts pool. Planners will know how many spares to stock to achieve short- and long-term service level requirements and, in operational settings, whether to wait for repairs to be completed and returned to service or to purchase additional service spares from suppliers, avoiding unnecessary buying and equipment downtime.

Contact us to learn more how this functionality has helped our customers in the MRO, Field Service, Utility, Mining, and Public Transportation sectors to optimize their inventory. You can also download the Whitepaper here.

White Paper: What you Need to know about Forecasting and Planning Service Parts

This paper describes Smart Software’s patented methodology for forecasting demand, safety stocks, and reorder points on items such as service parts and components with intermittent demand, and provides several examples of customer success.