Forecast accuracy is a key metric by which to judge the quality of your demand planning process. (It’s not the only one. Others include timeliness and cost; See 5 Demand Planning Tips for Calculating Forecast Uncertainty.) Once you have forecasts, there are a number of ways to summarize their accuracy, usually designated by obscure three- or four-letter acronyms like MAPE, RMSE, and MAE. See Four Useful Ways to Measure Forecast Error for more detail.

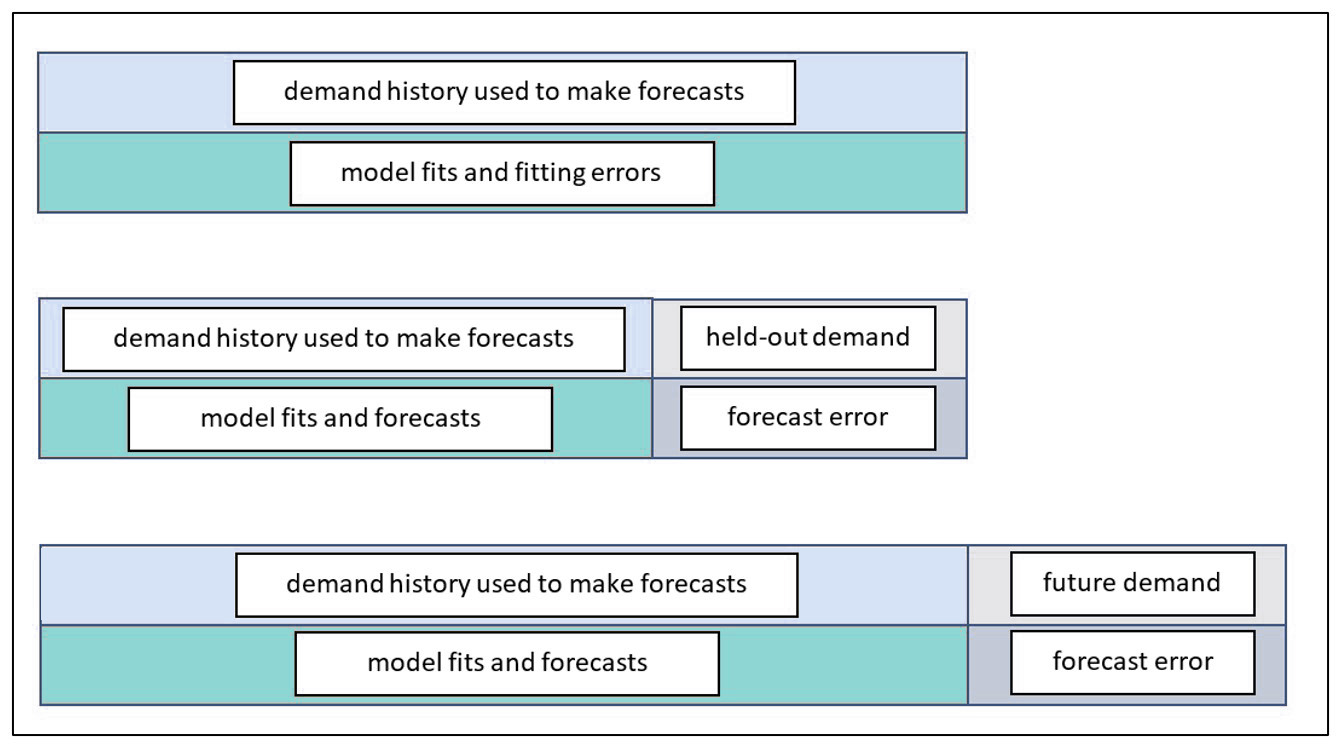

A less discussed but more fundamental issue is how computational experiments are organized for computing forecast error. This post compares the three most important experimental designs. One of them is old-school and essentially amounts to cheating. Another is the gold standard. A third is a useful expedient that mimics the gold standard and is best thought of as predicting how the gold standard will turn out. Figure 1 is a schematic view of the three methods.

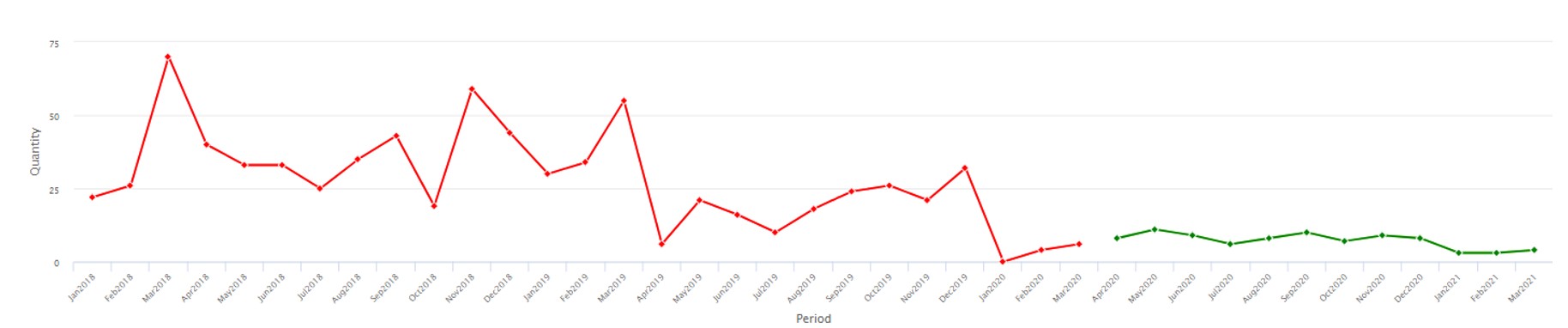

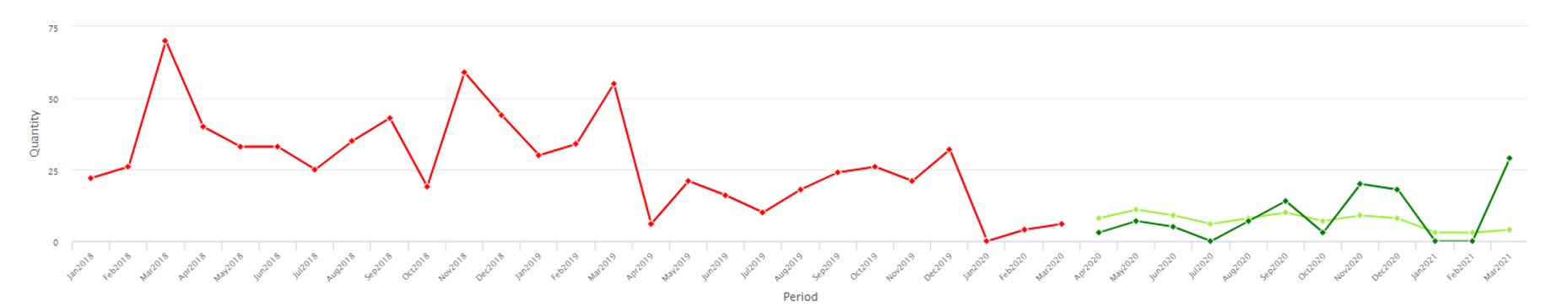

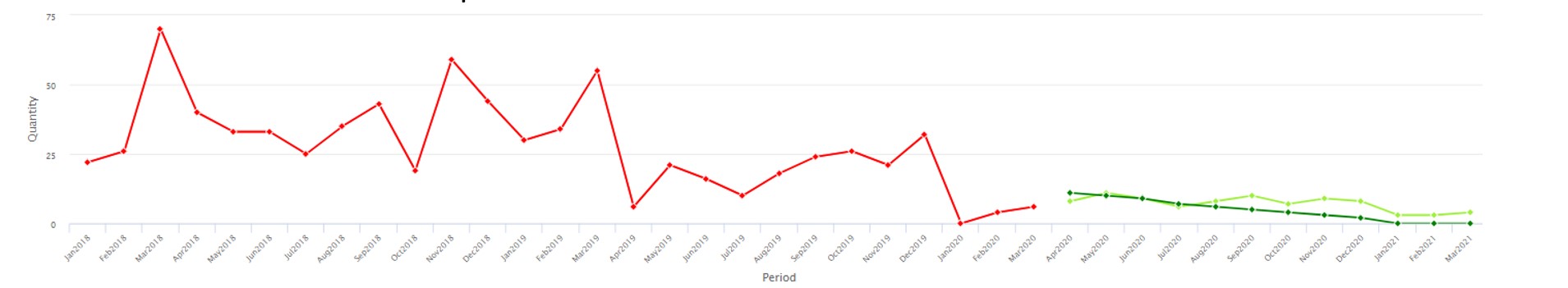

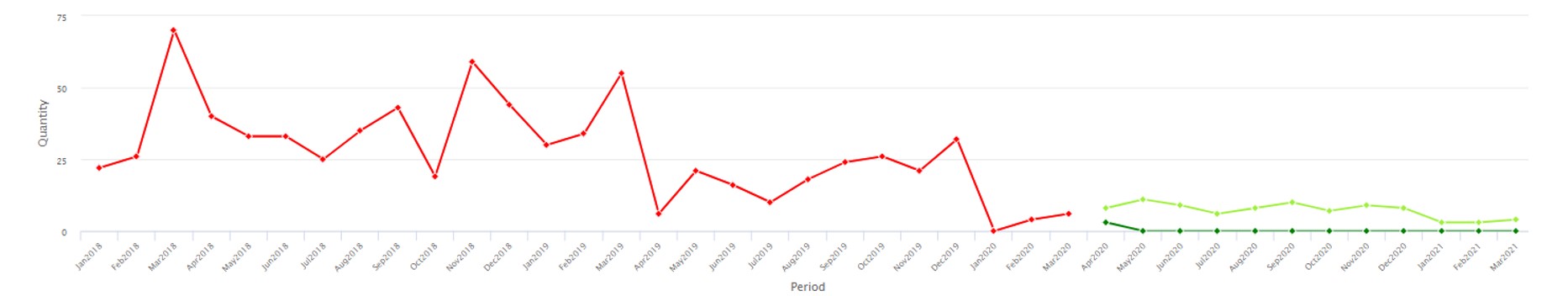

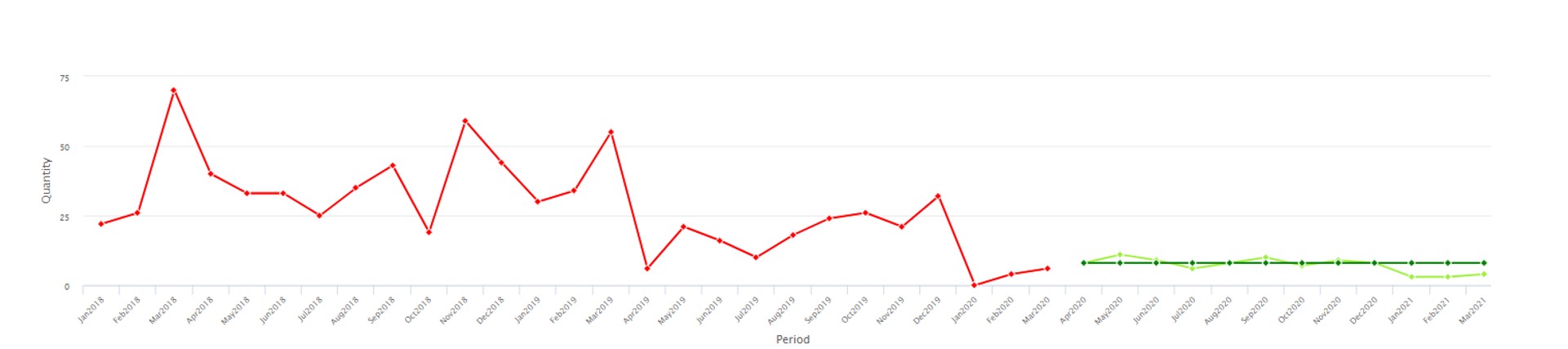

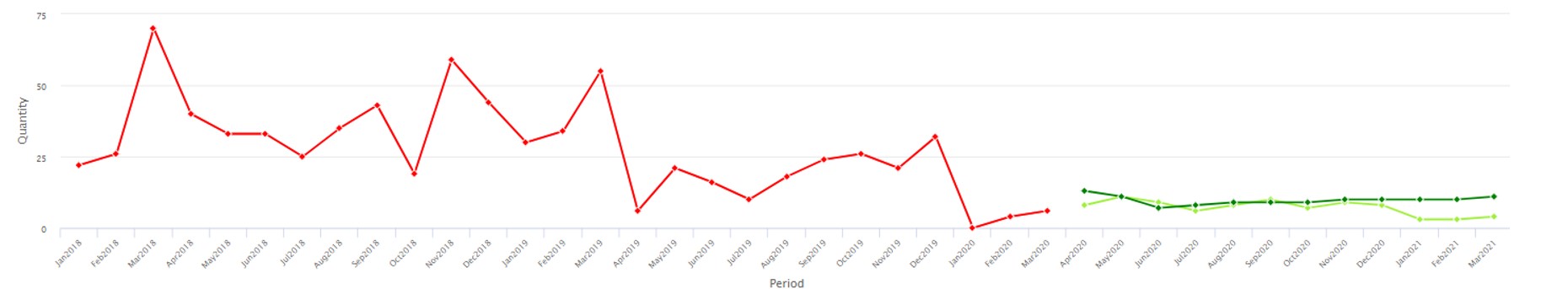

Figure 1: Three ways to assess forecast error

The top panel of Figure 1 depicts the way forecast error was assessed back in the early 1980’s before we moved the state of the art to the scheme shown in the middle panel. In the old days, forecasts were assessed on the same data used to compute the forecasts. After a model was fit to the data, the errors computed were not for model forecasts but for model fits. The difference is that forecasts are for future values, while fits are for concurrent values. For example, suppose the forecasting model is a simple moving average of the three most recent observations. At time 3, the model computes the average of observations 1, 2, and 3. This average would then be compared to the observed value at time 3. We call this cheating because the observed value at time 3 got a vote on what the forecast should be at time 3. A true forecast assessment would compare the average of the first three observations to the value of the next, fourth, observation. Otherwise, the forecaster is left with an overly optimistic assessment of forecast accuracy.

The bottom panel of Figure 1 shows the best way to assess forecast accuracy. In this schema, all the historical demand data are used to fit a model, which is then used to forecast future, unknown demand values. Eventually, the future unfolds, the true future values reveal themselves, and actual forecast errors can be computed. This is the gold standard. This information populates the “forecasts versus actuals” report in our software.

The middle panel depicts a useful halfway measure. The problem with the gold standard is that you must wait to learn how well your chosen forecasting methods perform. This delay does not help when you are required to choose, in the moment, which forecasting method to use for each item. Nor does it provide a timely estimate of the forecast uncertainty you will experience, which is important for risk management such as forecast hedging. The middle way is based on hold-out analysis, which excludes (“holds out”) the most recent observations and asks the forecasting method to do its work without knowing those ground truths. Then the forecasts based on the foreshortened demand history can be compared to the held-out actual values to get an honest assessment of forecast error.