Whether you are using ‘Min/Max’ or ‘reorder point’ and ‘order quantity’ to determine when and how much to restock, your approach might deliver or deny huge efficiencies. Key mistakes to avoid:

- Not recalibrating regularly

- Only reviewing Min/Max when there is a problem

- Using Forecasting methods not up to the task

- Assuming data is too slow moving or unpredictable for it to matter

“We have over 150,000 SKU x Location combinations. Our demand is intermittent. Since it’s slow moving, we don’t need to recalculate our reorder points often. We do so maybe once annually but review the reorder points whenever there is a problem.” – Materials Manager.

This reactive approach will lead to millions in excess stock, stock outs, and lots of wasted time reviewing data when “something goes wrong.” Yet, I’ve heard this same refrain from so many inventory professionals over the years. Clearly, we need to do more to share why this thinking is so problematic.

It is true that for many parts, a recalculation of the reorder points with up-to-date historical data and lead times might not change much, especially if patterns such as trend or seasonality aren’t present. However, many parts will benefit from a recalculation, especially if lead times or recent demand has changed. Plus, the likelihood of significant change that necessitates a recalculation increases the longer you wait. Finally, those months with zero demands also influence the probabilities and shouldn’t be ignored outright. The key point though is that it is impossible to know what will change or won’t change in your forecast, so it’s better to recalibrate regularly.

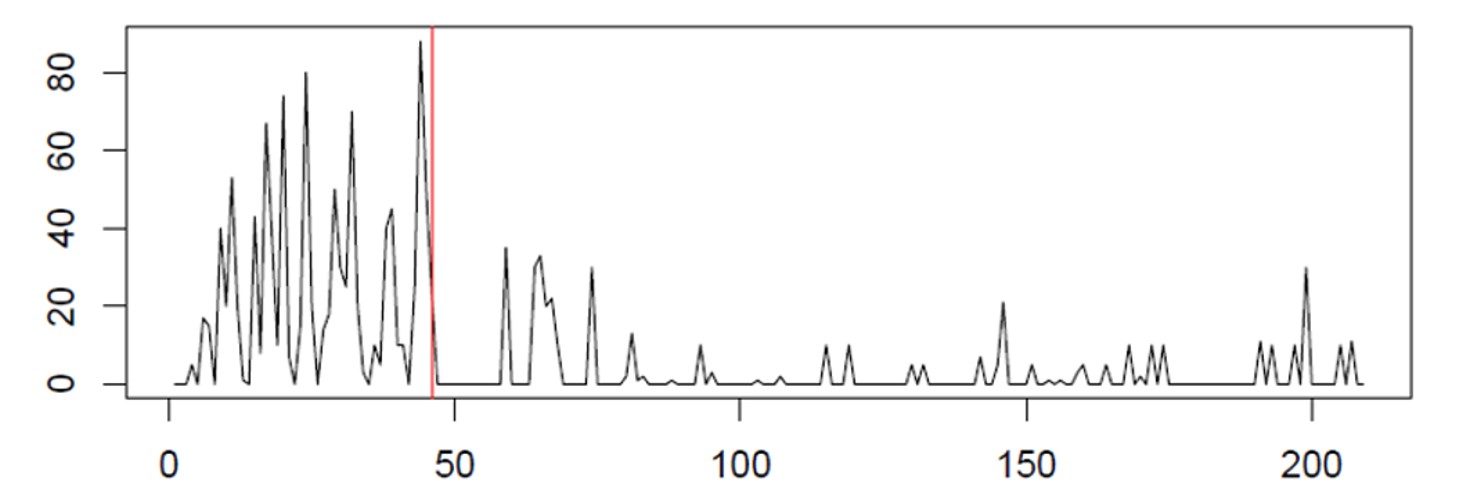

This standout case from real world data illustrates a scenario where regular and automated recalibration shines—the benefits from quick responses to changing demand patterns like these add up quickly. In the above example, the X axis represents days, and the Y axis represents demand. If you were to wait several months between recalibrating your reorder points, you’d undoubtedly order far too soon. By recalibrating your reorder point far more often, you’ll catch the change in demand enabling much more accurate orders.

Rather than wait until you have a problem, recalibrate all parts every planning cycle at least once monthly. Doing so takes advantage of the latest data and proactively adjusts the stocking policy, thus avoiding problems that would cause manual reviews and inventory shortages or excess.

The nature of your (potentially varied) data also needs to be matched with the right forecasting tools. If records for some parts show trend or seasonal patterns, using targeting forecasting methods to accommodate these patterns can make a big difference. Similarly, if the data show frequent zero values (intermittent demand), forecasting methods not built around this special case can easily deliver unreliable results.

Automate, recalibrate and review exceptions. Purpose built software will do this automatically. Think of it another way: is it better to dump a bunch of money into your 401K once per year or “dollar cost average” by depositing smaller, equally sized amounts throughout the year. Recalibrating policies regularly will yield maximized returns over time, just as dollar cost averaging will do for your investment portfolio.

How often do you recalibrate your stocking policies? Why?