You know the situation: You work out the best way to manage each inventory item by computing the proper reorder points and replenishment targets, then average demand increases or decreases, or demand volatility changes, or suppliers’ lead times change, or your own costs change. Now your old policies (reorder points, safety stocks, Min/Max levels, etc.) have been obsoleted – just when you think you’d got them right. Leveraging advanced planning and inventory optimization software gives you the ability to proactively address ever-changing outside influences on your inventory and demand. To do so, you’ll need to regularly recalibrate stocking parameters based on ever-changing demand and lead times.

Recently, some potential customers have expressed concern that by regularly modifying inventory control parameters they are introducing “noise” and adding complication to their operations. A visitor to our booth at last week’s Microsoft Dynamics User Group Conference commented:

“We don’t want to jerk around the operations by changing the policies too often and introducing noise into the system. That noise makes the system nervous and causes confusion among the buying team.”

This view is grounded in yesterday’s paradigms. While you should generally not change an immediate production run, ignoring near-term changes to the policies that drive future production planning and order replenishment will wreak havoc on your operations. Like it or not, the noise is already there in the form of extreme demand and supply chain variability. Fixing replenishment parameters, updating them infrequently, or only reviewing at the time of order means that your Supply Chain Operations will only be able to react to problems rather than proactively identify them and take corrective action.

Modifying the policies with near-term recalibrations is adapting to a fluid situation rather than being captive to it. We can look to this past weekend’s NFL games for a simple analogy. Imagine the quarterback of your favorite team consistently refusing to call an audible (change the play just before the ball is snapped) after seeing the defensive formation. This would result in lots of missed opportunities, inefficiency, and stalled drives that could cost the team a victory. What would you want your quarterback to do?

Demand, lead times, costs, and business priorities often change, and as these last 18 months have proved they often change considerably. As a Supply Chain leader, you have a choice: keep parameters fixed resulting in lots of knee-jerk expedites and order cancellations, or proactively modify inventory control parameters. Calling the audible by recalibrating your policies as demand and supply signals change is the right move.

Here is an example. Suppose you are managing a critical item by controlling its reorder point (ROP) at 25 units and its order quantity (OQ) at 48. You may feel like a rock of stability by holding on to those two numbers, but by doing so you may be letting other numbers fluctuate dramatically. Specifically, your future service levels, fill rates, and operating costs could all be resetting out of sight while you fixate on holding onto yesterday’s ROP and OQ. When the policy was originally determined, demand was stable and lead times were predictable, yielding service levels of 99% on an important item. But now demand is increasing and lead times are longer. Are you really going to expect the same outcome (99% service level) using the same sets of inputs now that demand and lead times are so different? Of course not. Suppose you knew that given the recent changes in demand and lead time, in order to achieve the same service level target of 99%, you had to increase the ROP to 35 units. If you were to keep the ROP at 25 units your service level would fall to 92%. Is it better to know this in advance or to be forced to react when you are facing stockouts?

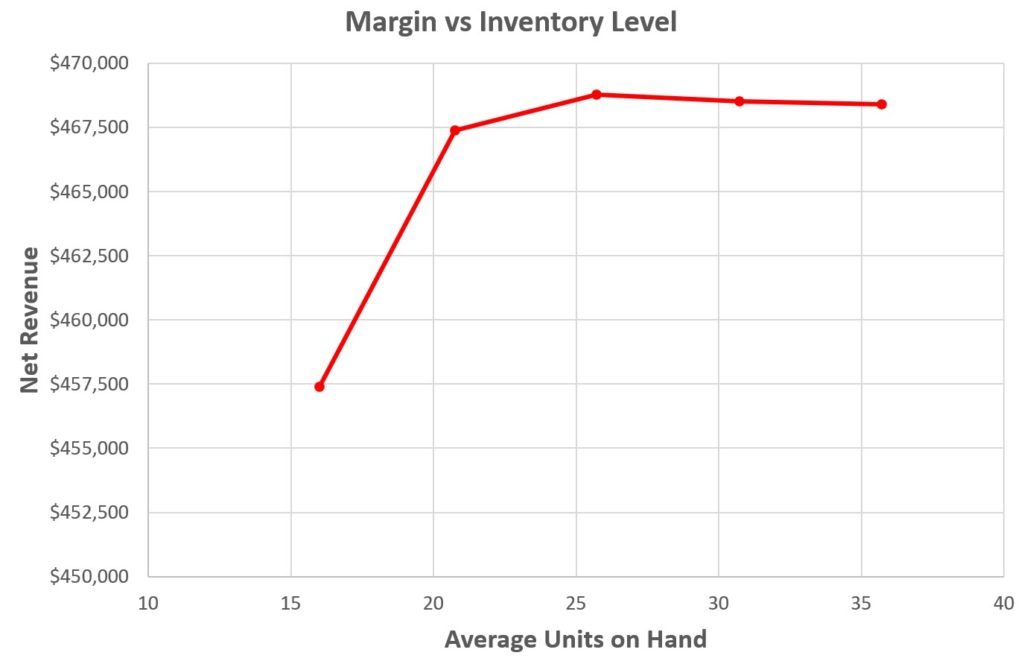

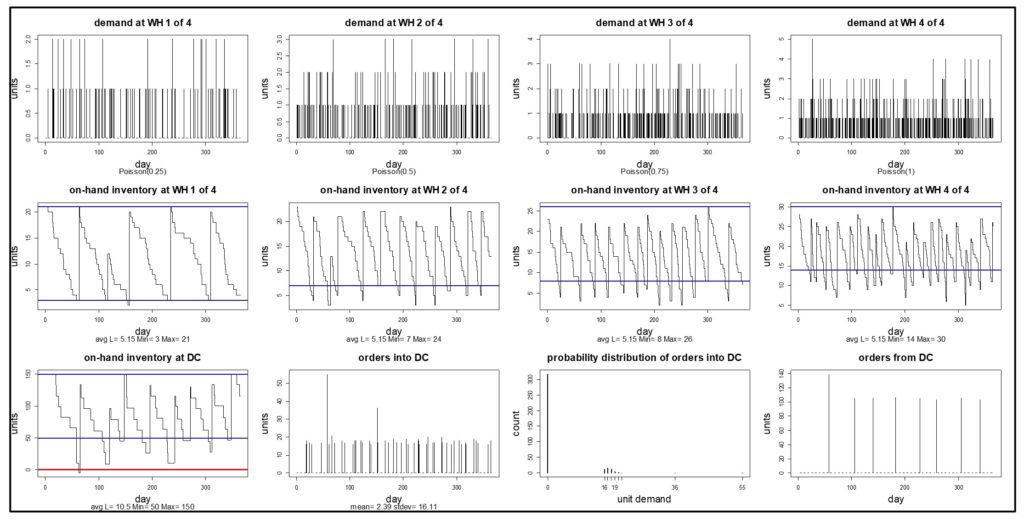

What inventory optimization and planning software does is make visible the connections between performance metrics like service rate and control parameters like ROP and ROQ. The invisible becomes visible, allowing you to make reasoned adjustments that keep your metrics where you need them to be by adjusting the control levers available for your use. Using probabilistic forecasting methods will enable you to generate Key Performance Predictions (KPPs) of performance and costs while identifying near-term corrective actions such as targeted stock movements that help avoid problems and take advantage of opportunities. Not doing so puts your supply chain planning in a straightjacket, much like the quarterback who refuses to audible.

Admittedly, a constantly-changing business environment requires constant vigilance and occasional reaction. But the right inventory optimization and demand forecasting software can recompute your control parameters at scale with a few mouse clicks and clue your ERP system how to keep everything on course despite the constant turbulence. The noise is already in your system in the form of demand and supply variability. Will you proactively audible or stick to an older plan and cross your fingers that things will work out fine?

How to Forecast Inventory Requirements

Forecasting inventory requirements is a specialized variant of forecasting that focuses on the high end of the range of possible future demand. Traditional methods often rely on bell-shaped demand curves, but this isn’t always accurate. In this article, we delve into the complexities of this practice, especially when dealing with intermittent demand.

Explaining What “Service Level” Means in Your Inventory Optimization Software

Navigating the intricacies of stocking recommendations can often lead to questions about their accuracy and significance. A recent inquiry from one of our customers prompted an insightful discussion on the nuances of service levels and reorder points. During a team meeting, we identified unusual gaps between our Smart-suggested reorder points (ROP) at a 99% service level and the customer’s current ROP. In this post, we unravel the concept of a “99% service level” and its implications for inventory optimization, shedding light on how timing and immediate stock availability play pivotal roles in meeting customer expectations and remaining competitive in diverse industries.

Don’t blame shortages on problematic lead times.

Lead time delays and supply variability are supply chain facts of life, yet inventory-carrying organizations are often caught by surprise when a supplier is late. An effective inventory planning process embraces this fact of life and develops policies that effectively account for this uncertainty. Sure, there will be times when lead time delays come out of nowhere and cause a shortage. But most often, the shortages result from: