We often encounter Excel-based reorder point planning methods. In this post, we’ve detailed an approach that a customer used prior to proceeding with Smart. We describe how their spreadsheet worked, the statistical approaches it relied on, the steps planners went through each planning cycle, and their stated motivations for using (and really liking) this internally developed spreadsheet.

Their monthly process consisted of updating a new month of actuals into the “reorder point sheet.” An embedded formula recomputed the Reorder Point (ROP) and order-up-to (Max) level. It worked like this:

- ROP = LT Demand + Safety Stock

- LT Demand = average daily demand x lead time days (assumed constant to keep things simple)

- Safety Stock for long lead time parts = Standard deviation x 2.0

- Safety Stock for short lead time parts = Standard deviation x 1.2

- Max = ROP + supplier-dictated Minimum Order Quantity

Historical averages and standard deviations used 52-weeks of rolling history (i.e., the newest week replaced the oldest week each period). The standard deviation of demand was computed using the “stdevp” function in Excel.

Every month, a new ROP was recomputed. Both the average demand and standard deviation were modified by the new week’s demand, which in turn updated the ROP.

The default ROP is always based on the above logic. However, planners would make changes under certain conditions:

1. Planners would increase the Min for inexpensive parts to reduce risk of taking an on-time delivery hit (OTD) on an inexpensive part.

2. The Excel sheet identified any part with a newly calculated ROP that was ± 20% different from the current ROP.

3. Planners reviewed parts that exceed the exception threshold, proposed changes, and got a manager to approve.

4. Planners reviewed items with OTD hits and increased the ROP based on their intuition. Planners continued to monitor those parts for several periods and lowered the ROP when they felt it is safe.

5. Once the ROP and Max quantity were determined, the file of revised results was sent to IT, who uploaded into their ERP.

6. The ERP system then managed daily replenishment and order management.

Objectively, this was perhaps an above-average approach to inventory management. For instance, some companies are unaware of the link between demand variability and safety stock requirements and rely on rule of methods or intuition exclusively. However, there are problems with their approach:

1. Manual data updates

The spreadsheets required manual updating. To recompute, multiple steps were required, each with their own dependency. First, a data dump needed to be run from the ERP system. Second, a planner would need to open the spreadsheet and review it to make sure the data imported properly. Third, they needed to review output to make sure it calculated as expected. Fourth, manual steps were required to push the results back to the ERP system.

2. One Size Fits All Safety Stock

Or in this case, “one of two sizes fit all”. The choice of using 2x and 1.2x standard deviation for long and short lead time items respectively equates to service levels of 97.7% and 88.4%. This is a big problem since it stands to reason that not every part in each group requires the same service level. Some parts will have higher stock out pain than others and vice versa. Service levels should therefore be specified accordingly and be commensurate with the importance of the item. We discovered that they were experiencing OTD hits on roughly 20% of their critical spare parts which necessitated manual overrides of the ROP. The root cause was that on all short lead time items they they were planning for an 88.4% service level target. So, the best they could have gotten was to stock out 12% of the time even if “on plan.” It would have been better to plan service level targets according to the importance of the part.

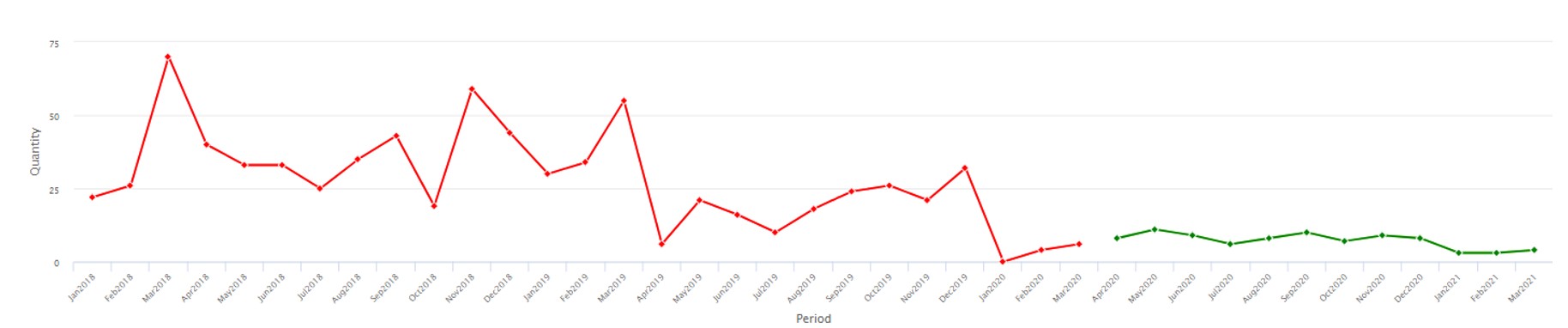

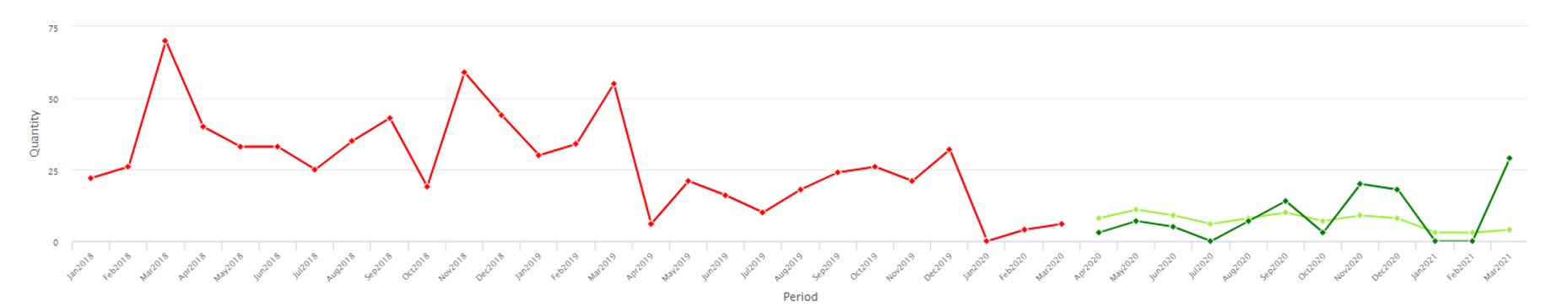

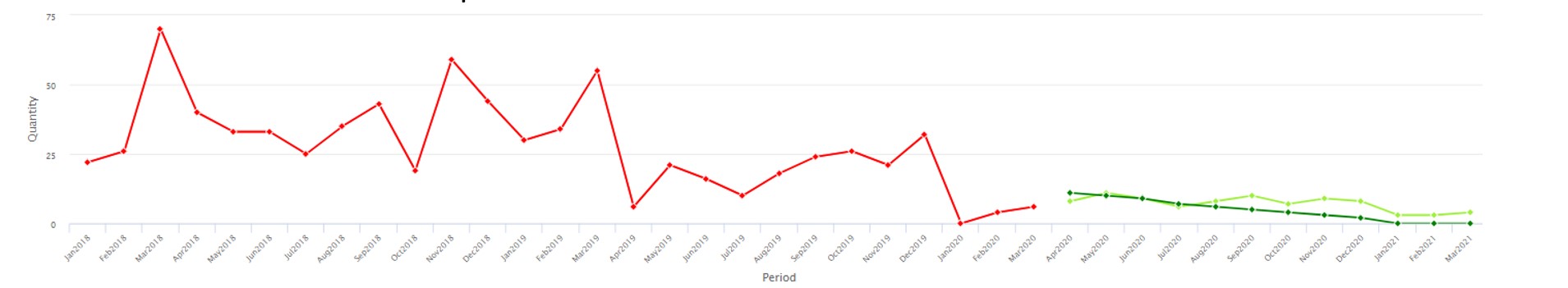

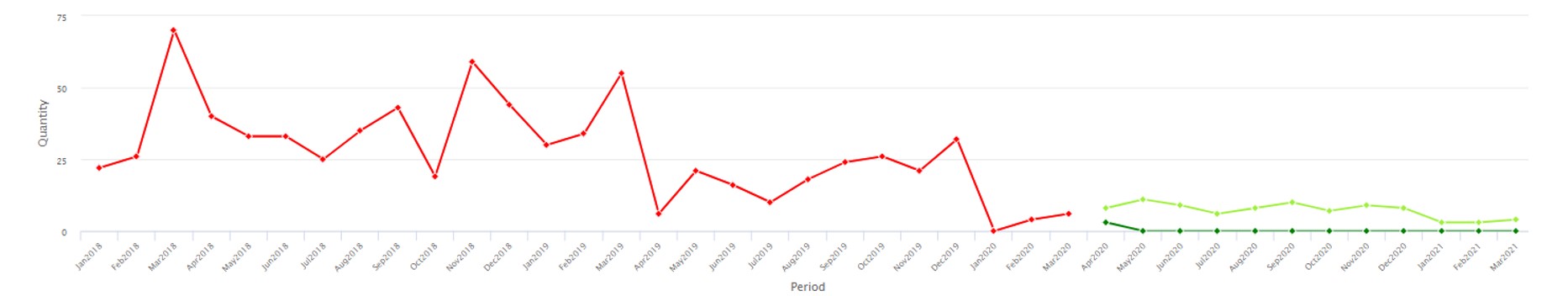

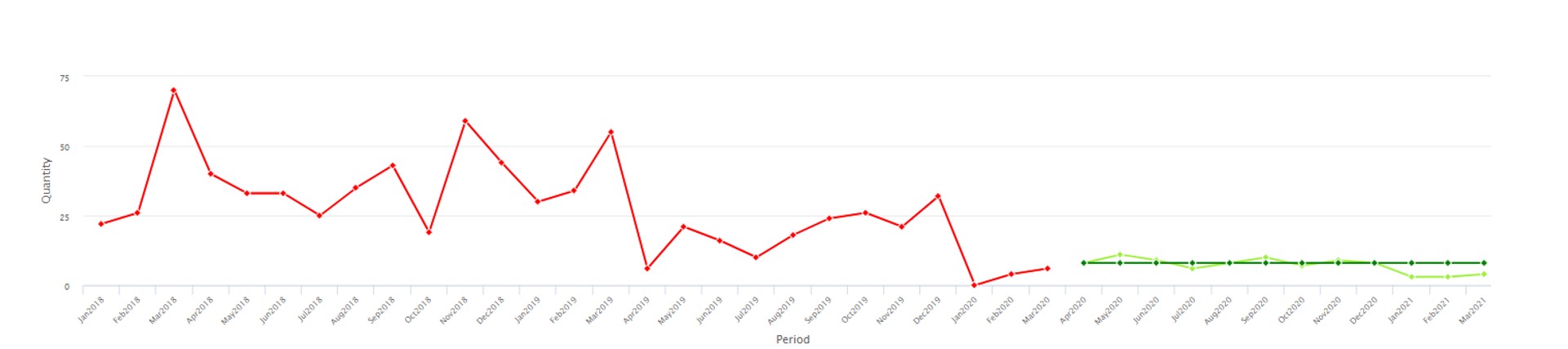

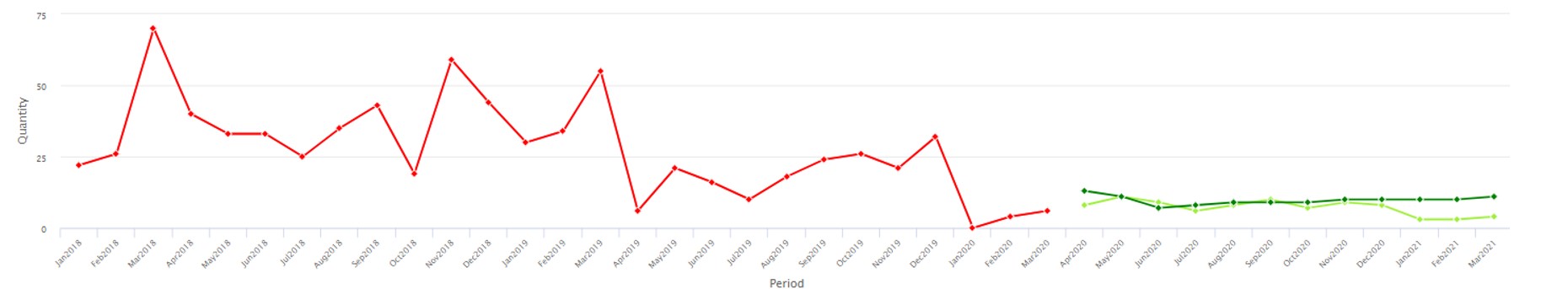

3. Safety stock is inaccurate. The items being planned for this company are spare parts to support diagnostic equipment. The demand on most of these parts is very intermittent and sporadic. So, the choice of using an average to compute lead time demand wasn’t unreasonable if you accept the need for ignoring variability in lead times. However, the reliance on a Normal distribution to determine the safety stock was a big mistake that resulted in inaccurate safety stocks. The company stated that its service levels for long lead time items ran in the 90% range compared to their target of 97.7%, and that they made up the difference with expedites. Achieved service levels for shorter lead time items were about 80%, despite being targeted for 88.4%. They computed safety stock incorrectly because their demand isn’t “bell shaped” yet they picked safety stocks assuming they were. This simplification results in missing service level targets, forcing the manual review of many items that then need to be manually “monitored for several periods” by a planner. Wouldn’t it be better to make sure the reorder point met the exact service level you wanted from the start? This would ensure you hit your service levels while minimizing unneeded manual intervention.

There is a fourth issue that didn’t make the list but is worth mentioning. The spreadsheet was unable to track trend or seasonal patterns. Historical averages ignore trend and seasonality, so the cumulative demand over lead time used in the ROP will be substantially less accurate for trending or seasonal parts. The planning team acknowledged this but didn’t feel it was a legitimate issue, reasoning that most of the demand was intermittent and didn’t have seasonality. It is important for the model to pick up on trend and seasonality on intermittent data if it exists, but we didn’t find their data exhibited these patterns. So, we agreed that this wasn’t an issue for them. But as planning tempo increases to the point that demand is bucketed daily, even intermittent demand very often turns out to have day-of-week and sometimes week-of-month seasonality. If you don’t run at a higher frequency now, be aware that you may be forced to do so soon to keep up with more agile competition. At that point, spreadsheet-based processing will just not be able to keep up.

In conclusion, don’t use spreadsheets. They are not conducive to meaningful what-if analyses, they are too labor-intensive, and the underlying logic must be dumbed down to process quickly enough to be useful. In short, go with purpose-built solutions. And make sure they run in the cloud.

Spare Parts Planning Software solutions

Smart IP&O’s service parts forecasting software uses a unique empirical probabilistic forecasting approach that is engineered for intermittent demand. For consumable spare parts, our patented and APICS award winning method rapidly generates tens of thousands of demand scenarios without relying on the assumptions about the nature of demand distributions implicit in traditional forecasting methods. The result is highly accurate estimates of safety stock, reorder points, and service levels, which leads to higher service levels and lower inventory costs. For repairable spare parts, Smart’s Repair and Return Module accurately simulates the processes of part breakdown and repair. It predicts downtime, service levels, and inventory costs associated with the current rotating spare parts pool. Planners will know how many spares to stock to achieve short- and long-term service level requirements and, in operational settings, whether to wait for repairs to be completed and returned to service or to purchase additional service spares from suppliers, avoiding unnecessary buying and equipment downtime.

Contact us to learn more how this functionality has helped our customers in the MRO, Field Service, Utility, Mining, and Public Transportation sectors to optimize their inventory. You can also download the Whitepaper here.

White Paper: What you Need to know about Forecasting and Planning Service Parts

This paper describes Smart Software’s patented methodology for forecasting demand, safety stocks, and reorder points on items such as service parts and components with intermittent demand, and provides several examples of customer success.