Is safety stock regarded as emergency spares or as a day-to-day buffer against spikes in demand? Knowing the difference and configuring your ERP properly will make a big difference to your bottom line.

The Safety Stock field in your ERP system can mean very different things depending on the configuration. Not understanding these differences and how they impact your bottom line is a common issue we’ve seen arise in implementations of our software.

Implementing inventory optimization software starts with new customers completing the technical implementation to get data flowing. They then receive user training and spend weeks carefully configuring their initial safety stocks, reorder levels, and consensus demand forecasts with Smart IP&O. The team becomes comfortable with Smart’s key performance predictions (KPPs) for service levels, ordering costs, and inventory on hand, all of which are forecasted using the new stocking policies.

But when they save the policies and forecasts to their ERP test system, sometimes the orders being suggested are far larger and more frequent than they expected, driving up projected inventory costs.

When this happens, the primary culprit is how the ERP is configured to treat safety stock. Being aware of these configuration settings will help planning teams better set expectations and achieve the expected outcomes with less effort (and cause for alarm!).

Here are the three common examples of ERP safety stock configurations:

Configuration 1. Safety Stock is treated as emergency stock that can’t be consumed. If a breach of safety stock is predicted, the ERP system will force an expedite no matter the cost so the inventory on hand never falls below safety stock, even if a scheduled receipt is already on order and scheduled to arrive soon.

Configuration 2. Safety Stock is treated as Buffer stock that is designed to be consumed. The ERP system will place an order when a breach of safety stock is predicted but on hand inventory will be allowed to fall below the safety stock. The buffer stock protects against stockout during the resupply period (i.e., the lead time).

Configuration 3. Safety Stock is ignored by the system and treated as a visual planning aid or rule of thumb. It is ignored by supply planning calculations but used by the planner to help make manual assessments of when to order.

Note: We never recommend using the safety stock field as described in Configuration 3. In most cases, these configurations were not intended but result from years of improvisation that have led to using the ERP in a non-standard way. Generally, these fields were designed to programmatically influence the replenishment calculations. So, the focus of our conversation will be on Configurations 1 and 2.

Forecasting and inventory optimization systems are designed to compute forecasts that will anticipate inventory draw down and then calculate safety stocks sufficient to protect against variability in demand and supply. This means that the safety stock is intended to be used as a protective buffer (Configuration 2) and not as emergency sparse (Configuration 3). It is also important to understand that, by design, the safety stock will be consumed approximately 50% of the time.

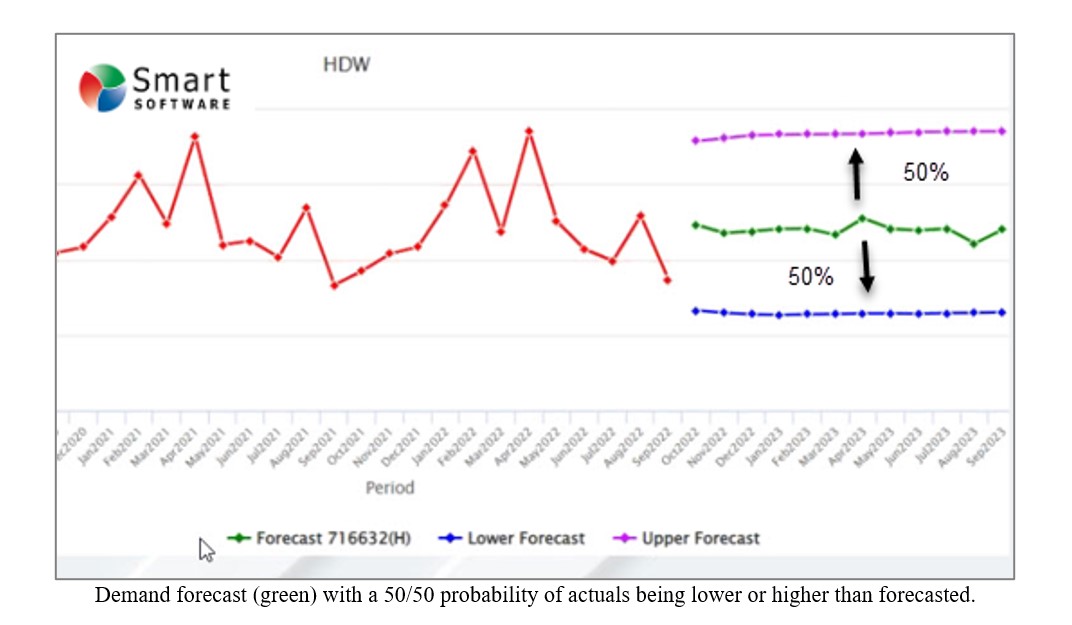

Why 50%? Because actual orders will exceed an unbiased forecast half of the time. See the graphic below illustrating this. A “good” forecast should yield the value that will come closest to the actual most often so actual demand will either be higher or lower without bias in either direction.

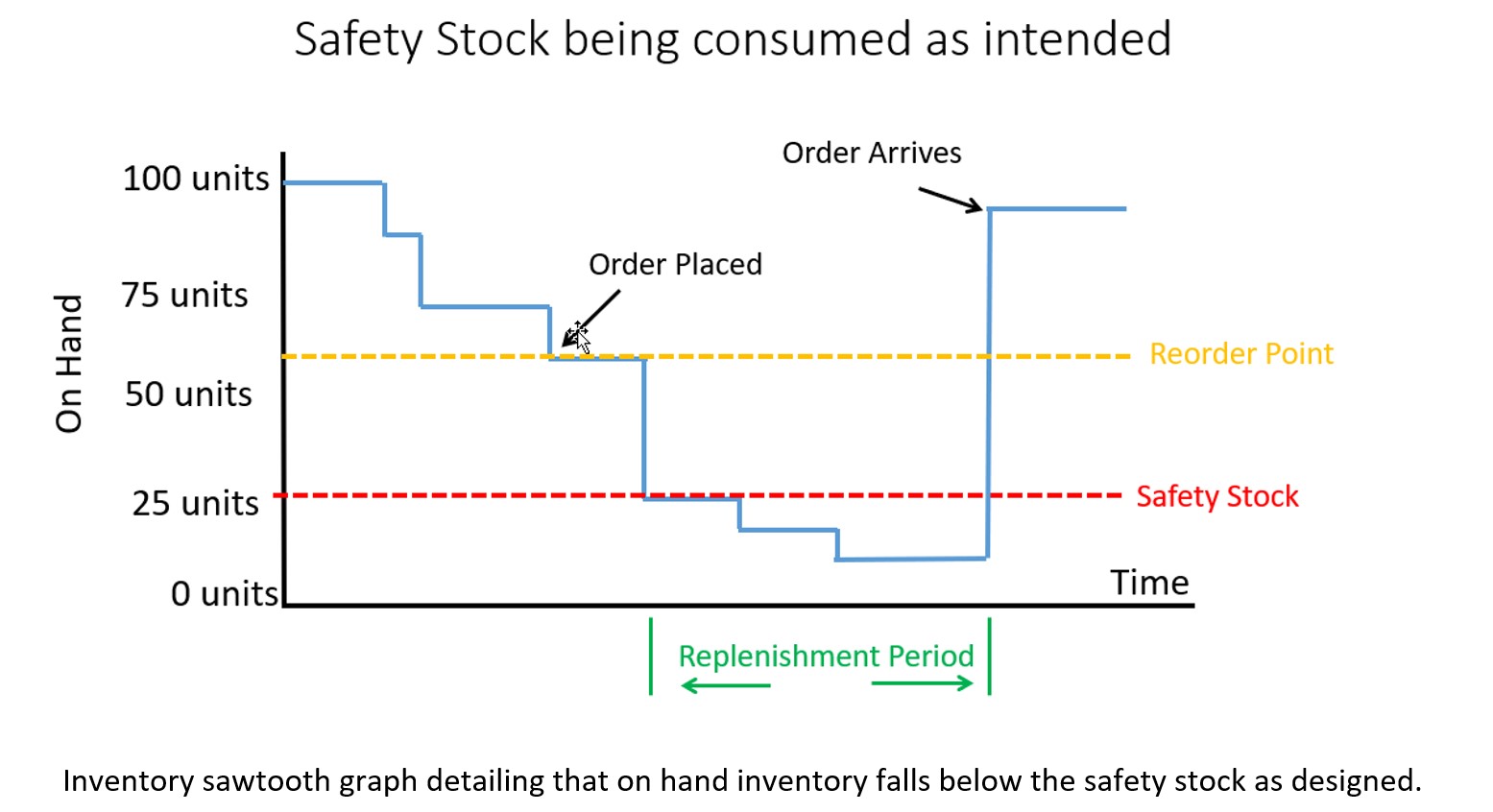

If you configured your ERP system to properly allow consumption of safety stock, then the on hand inventory might look like the graph below. Note that some safety stock is consumed but avoided a stockout. The service level you target when computing safety stock will dictate how often you stockout before the replenishment order arrives. Average inventory is roughly 60 units over the time horizon in this scenario.

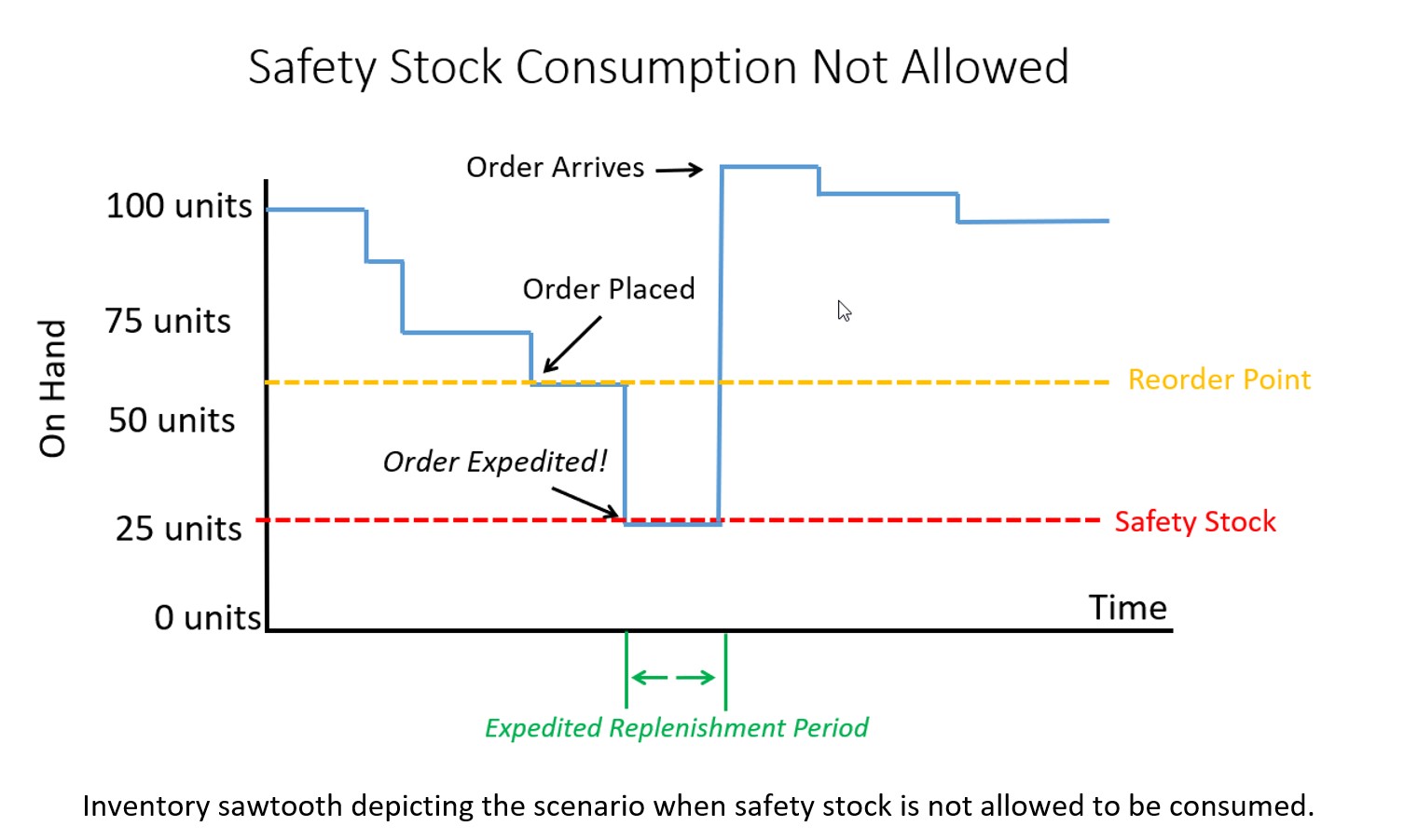

If your ERP system is configured to not allow consumption of safety stock and treats the quantity entered in the safety stock field more like emergency spares, then you will have a massive overstock! Your inventory on hand would look like the graph below with orders being expedited as soon as a breach of safety stock is expected. Average inventory is roughly 90 units, a 50% increase compared to when you allowed safety stock to be consumed.