Are you confused about what is AI and what is machine learning? Are you unsure why knowing more will help you with your job in inventory planning? Don’t despair. You’ll be ok, and we’ll show you how some of whatever-it-is can be useful.

What is and what isn’t

What is AI and how does it differ from ML? Well, what does anybody do these days when they want to know something? They Google it. And when they do, the confusion starts.

One source says that the neural net methodology called deep learning is a subset of machine learning, which is a subset of AI. But another source says that deep learning is already a part of AI because it sort of mimics the way the human mind works, while machine learning doesn’t try to do that.

One source says there are two types of machine learning: supervised and unsupervised. Another says there are four: supervised, unsupervised, semi-supervised and reinforcement.

Some say reinforcement learning is machine learning; others call it AI.

Some of us traditionalists call a lot of it “statistics”, though not all of it is.

In the naming of methods, there is a lot of room for both emotion and salesmanship. If a software vendor thinks you want to hear the phrase “AI”, they may well say it for you just to make you happy.

Better to focus on what comes out at the end

You can avoid some confusing hype if you focus on the end result you get from some analytic technology, regardless of its label. There are several analytical tasks that are relevant to inventory planners and demand planners. These include clustering, anomaly detection, regime change detection, and regression analysis. All four methods are usually, but not always, classified as machine learning methods. But their algorithms can come straight out of classical statistics.

Clustering

Clustering means grouping together things that are similar and distancing them from things that are dissimilar. Sometimes clustering is easy: to separate your customers geographically, simply sort them by state or sales region. When the problem is not so dead obvious, you can use data and clustering algorithms to get the job done automatically even when dealing with massive datasets.

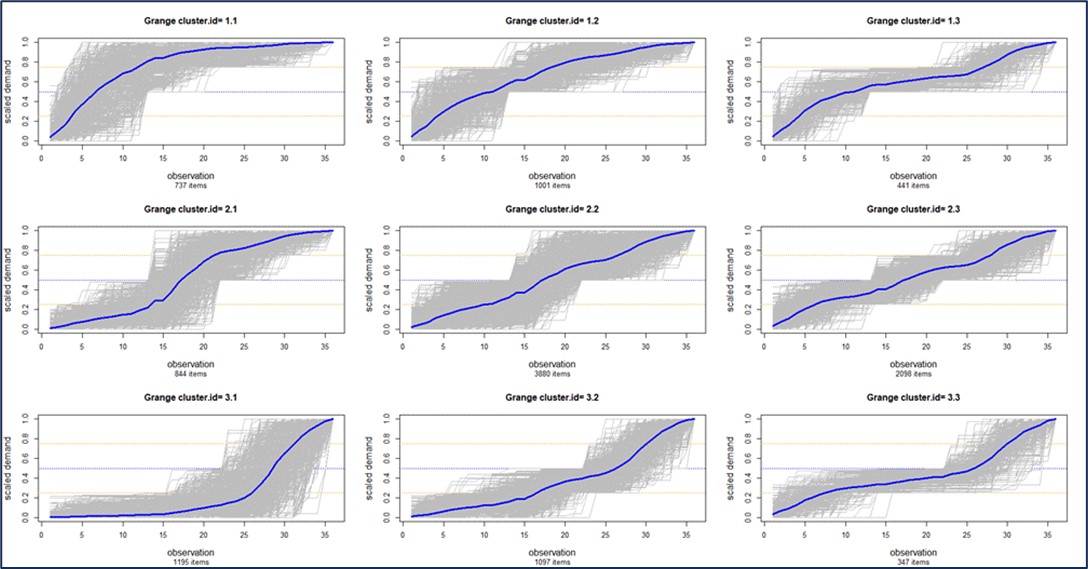

For example, Figure 1 illustrates a cluster of “demand profiles”, which in this case divides all a customer’s items into nine clusters based on the shape of their cumulative demand curves. Cluster 1.1 in the top left contains items whose demand has been petering out, while Cluster 3.1 in the bottom left contains items whose demand has accelerated. Clustering can also be done on suppliers. The choice of number of clusters is typically left to user judgement, but ML can guide that choice. For example, a user might instruct the software to “break my parts into 4 clusters” but using ML may reveal that there are really 6 distinct clusters the user should analyze.

Figure 1: Clustering items based on the shapes of their cumulative demand

Anomaly Detection

Demand forecasting is traditionally done using time series extrapolation. For instance, simple exponential smoothing works to find the “middle” of the demand distribution at any time and project that level forward. However, if there has been a sudden, one-time jump up or down in demand in the recent past, that anomalous value can have a significant but unwelcome effect on the near-term forecast. Just as serious for inventory planning, the anomaly can have an outsized effect on the estimate of demand variability, which goes directly to the calculation of safety stock requirements.

Planners may prefer to find and remove such anomalies (and maybe do offline follow-up to find out the reason for the weirdness). But nobody with a big job to do will want to visually scan thousands of demand plots to spot outliers, expunge them from the demand history, then recalculate everything. Human intelligence could do that, but human patience would soon fail. Anomaly detection algorithms could do the work automatically using relatively straightforward statistical methods. You could call this “artificial intelligence” if you wish.

Regime Change Detection

Regime change detection is like the big brother of anomaly detection. Regime change is a sustained, rather than temporary, shift in one or more aspects of the character of a time series. While anomaly detection usually focuses on sudden shifts in mean demand, regime change could involve shifts in other features of the demand, such as its volatility or its distributional shape.

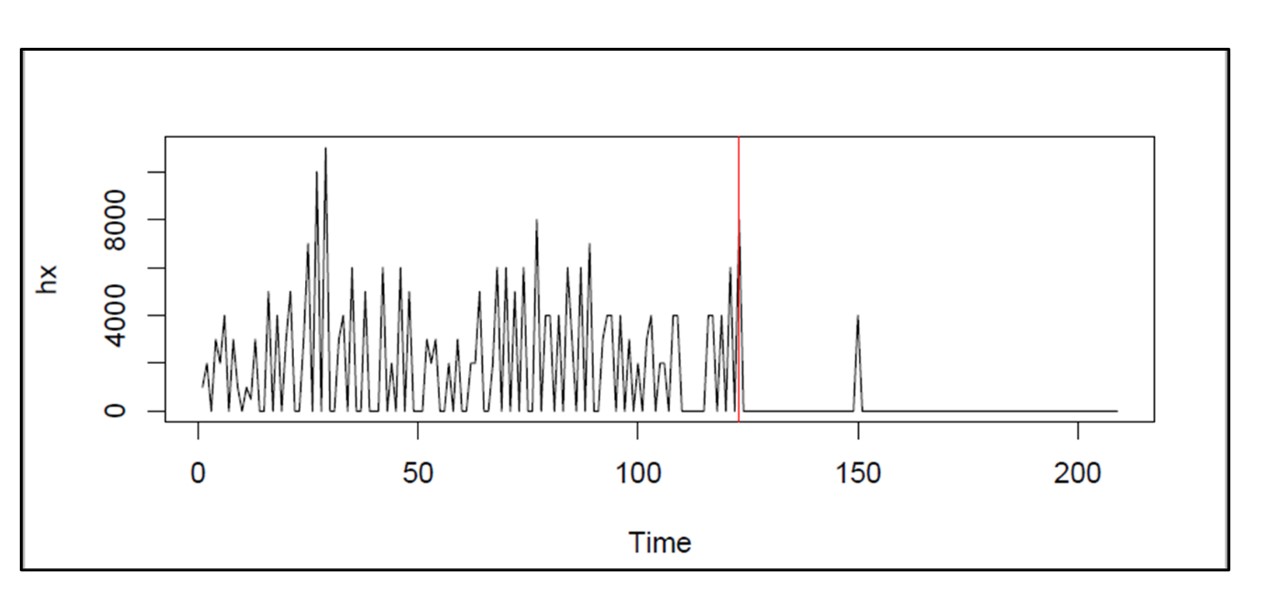

Figure 2 illustrates an extreme example of regime change. The bottom dropped out of demand for this item around day 120. Inventory control policies and demand forecasts based on the older data would be wildly off base at the end of the demand history.

Figure 2: An example of extreme regime change in an item with intermittent demand

Here too, statistical algorithms can be developed to solve this problem, and it would be fair play to call them “machine learning” or “artificial intelligence” if so motivated. Using ML or AI to identify regime changes in demand history enables demand planning software to automatically use only the relevant history when forecasting instead of having to manually pick the amount of history to introduce to the model.

Regression analysis

Regression analysis relates one variable to another through an equation. For example, sales of window frames in one month may be predicted from building permits issued a few months earlier. Regression analysis has been considered a part of statistics for over a century, but we can say it is “machine learning” since an algorithm works out the precise way to convert knowledge of one variable into a prediction of the value of another.

Summary

It is reasonable to be interested in what’s going on in the areas of machine learning and artificial intelligence. While the attention given to ChatGPT and its competitors is interesting, it is not relevant to the numerical side of demand planning or inventory management. The numerical aspects of ML and AI are potentially relevant, but you should try to see through the cloud of hype surrounding these methods and focus on what they can do. If you can get the job done with classical statistical methods, you might just do that, then exercise your option to stick the ML label on anything that moves.