Some companies invest in software to help them manage their inventory, whether it’s spare parts or finished goods. But a surprising number of others play the Inventory Guessing Game every day, trusting to an imagined “Golden Gut” or to plain luck to set their inventory control parameters. But what kind of results do you expect with that approach?

How good are you at intuiting the right values? This blog post challenges you to guess the best Min and Max values for a notional inventory item. We’ll show you its demand history, give you a few relevant facts, then you can pick Min and Max values and see how well they would work. Ready?

The Challenge

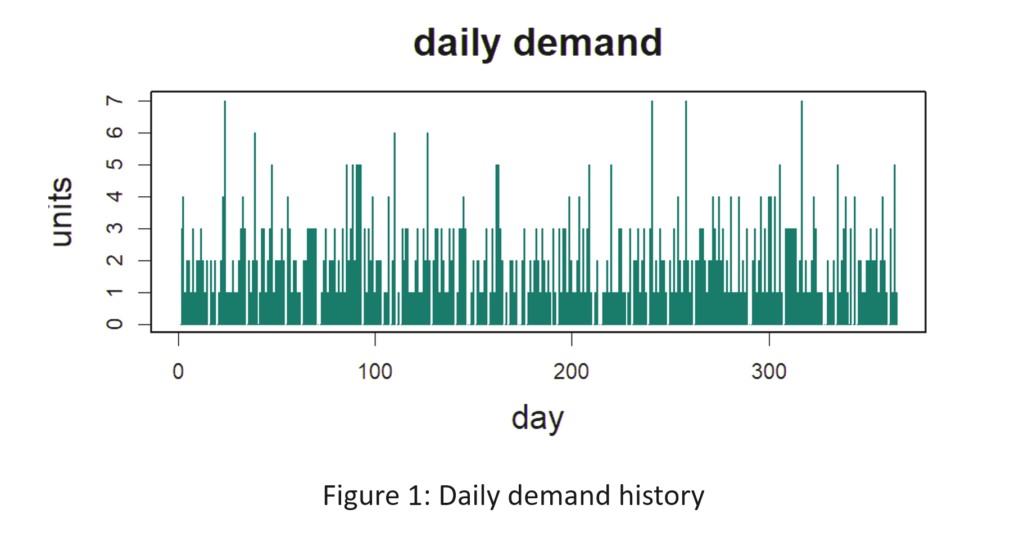

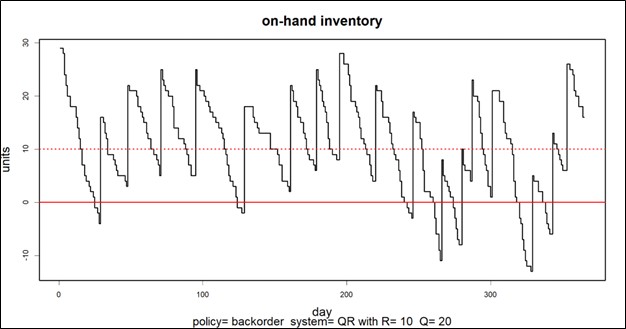

Figure 1 shows the daily demand history of the item. The average demand is 2 units per day. Replenishment lead time is a constant 10 days (which is unrealistic but works in your favor). Orders that cannot be filled immediately from stock cannot be backordered and are lost. You want to achieve at least an 80% fill rate, but not at any cost. You also want to minimize the average number of units on hand while still achieving at least an 80% fill rate. What Min and Max values would produce an 80% fill rate with the lowest average number of units on hand? [Record your answers for checking later. The solution appears below at the end of the article.]

Computing the Best Min and Max Values

The way to determine the best values is to use a digital twin, also known as a Monte Carlo simulation. The analysis creates a multitude of demand scenarios and passes them through the mathematical logic of the inventory control system to see what values will be taken on by key performance indicators (KPI’s).

We built a digital twin for this problem and systematically exercised it with 1,085 pairs of Min and Max values. For each pair, we simulated 365 days of operation a total of 100 times. Then we averaged the results to assess the performance of the Min/Max pair in terms of two KPI’s: fill rate and average on hand inventory.

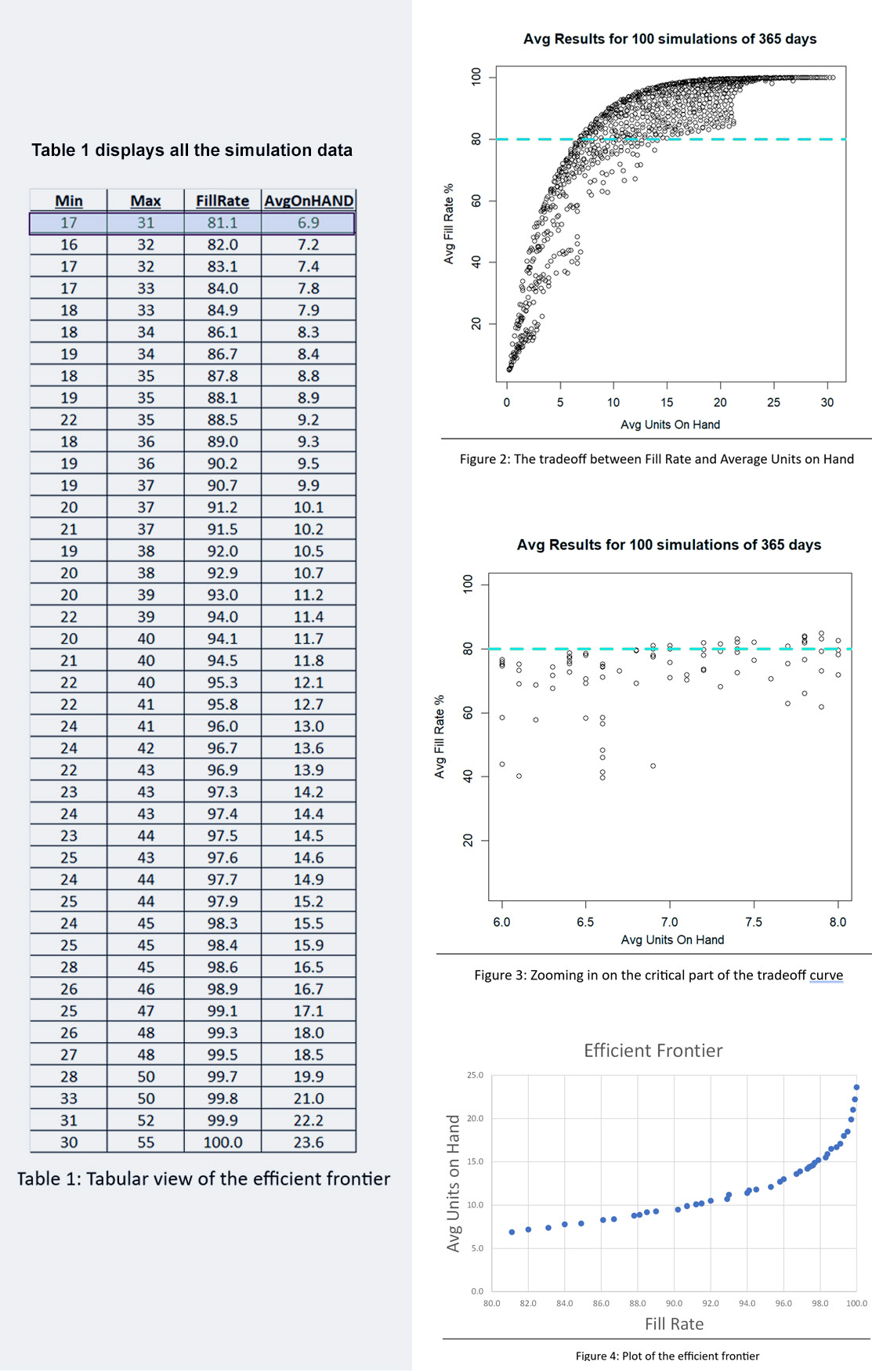

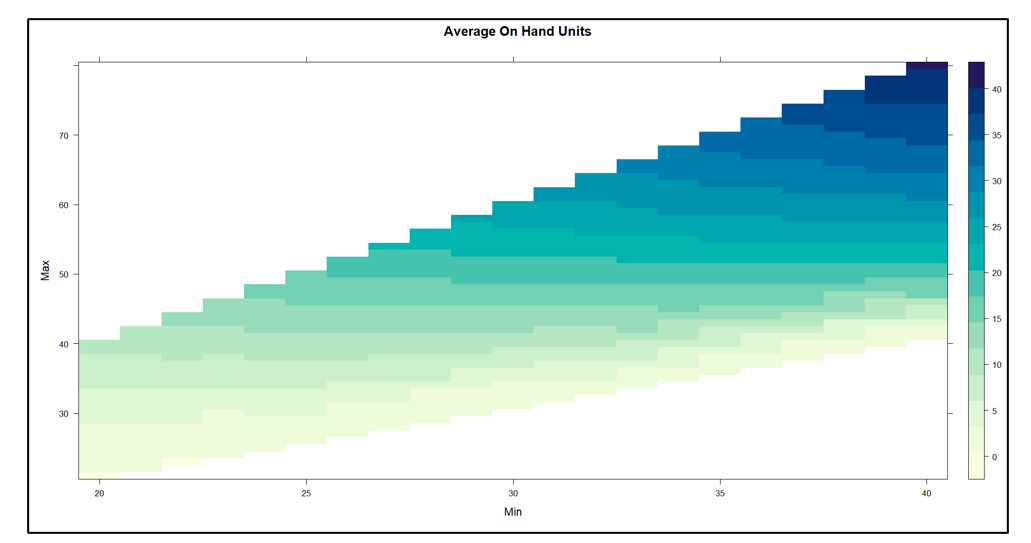

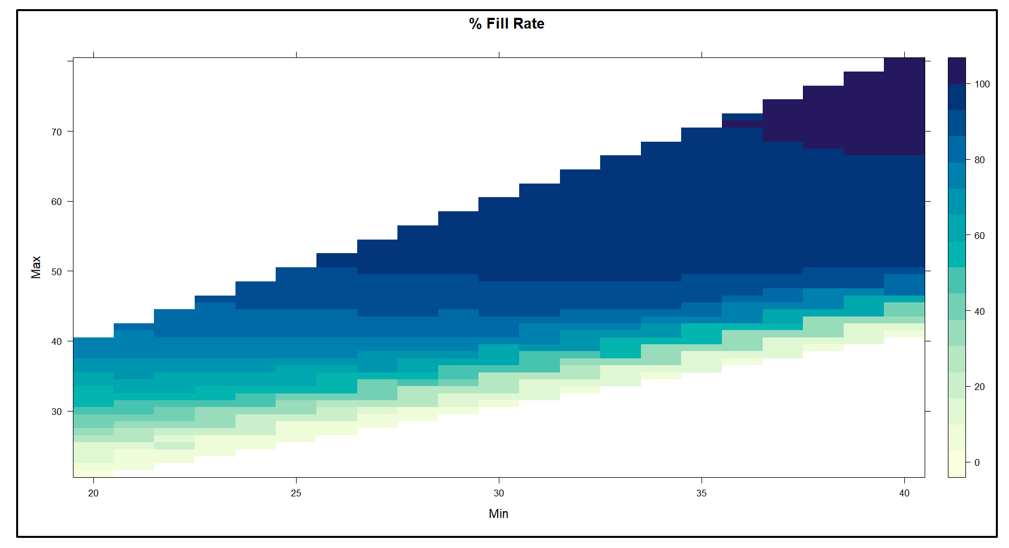

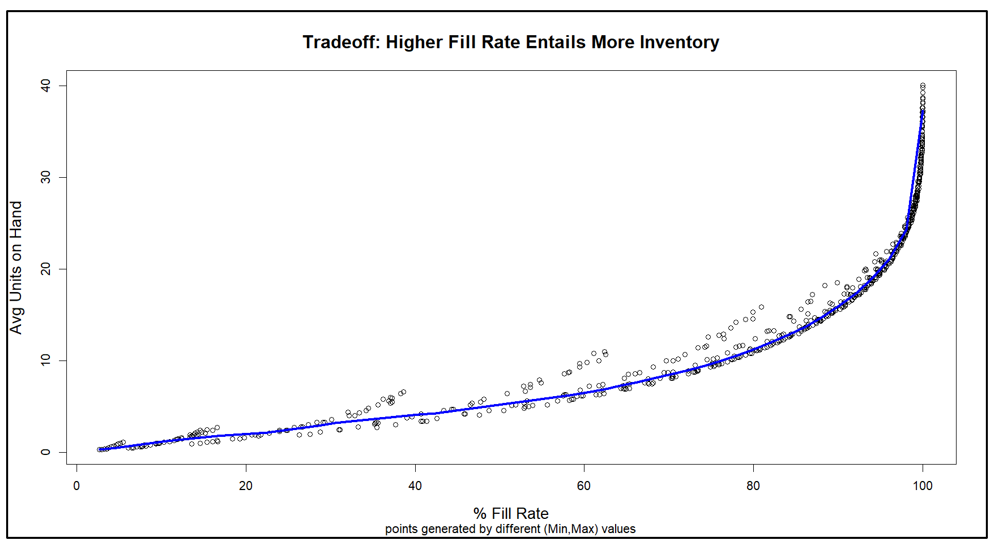

Figure 2 shows the results. The inherent tradeoff between inventory size and fill rate is clear in the figure: if you want a higher fill rate, you have to accept a larger inventory. However, at each level of inventory there is a range of fill rates, so the game is to find the Min/Max pair that yields the highest fill rate for any given size inventory.

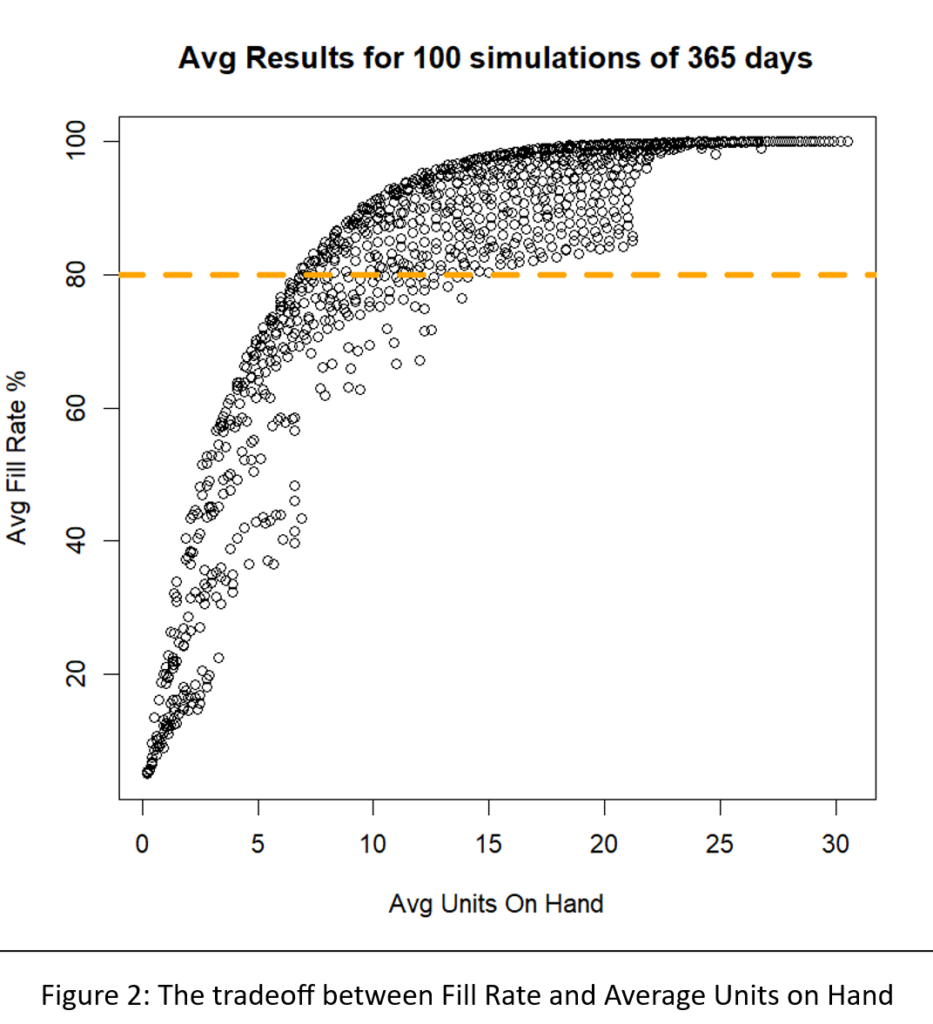

A different way to interpret Figure 2 is to focus on the dashed green line marking the target 80% fill rate. There are many Min/Max pairs that can hit near the 80% target, but they differ in inventory size from about 6 to about 8 units. Figure 3 zooms in on that region of Figure 2 to show quite a number of Min/Max pairs that are competitive.

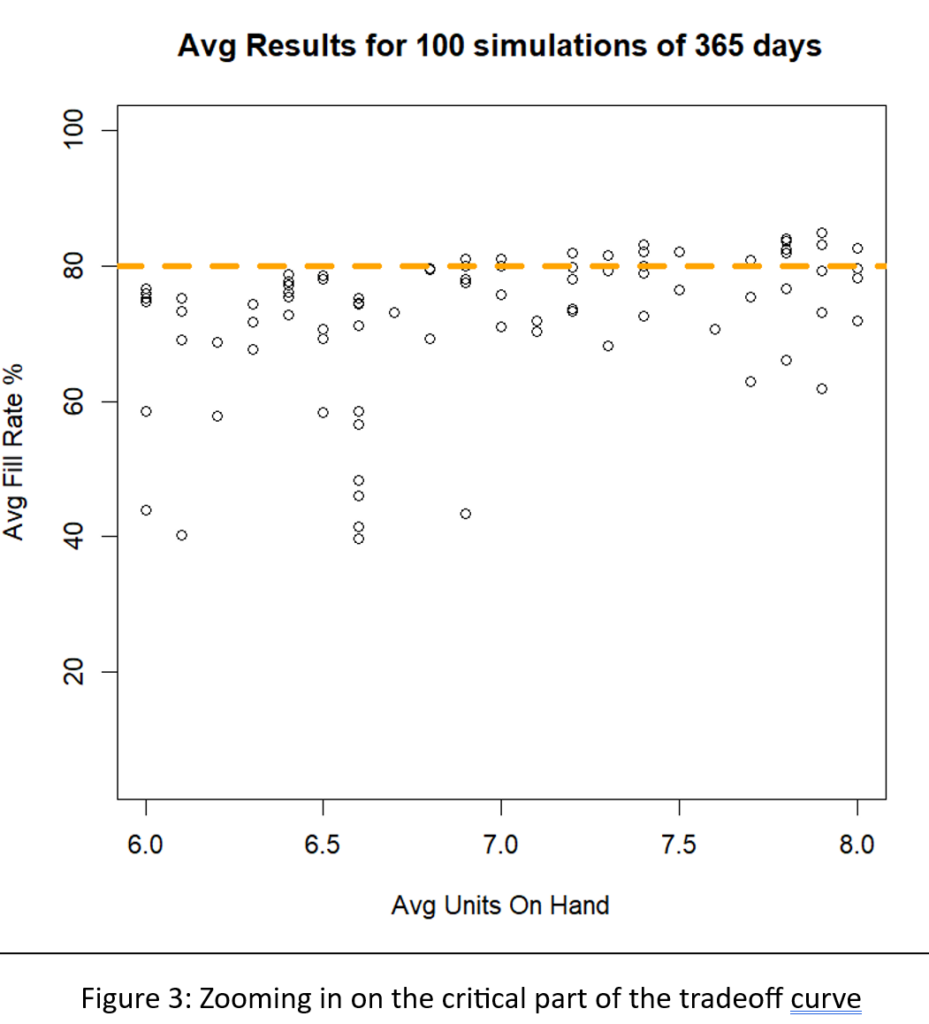

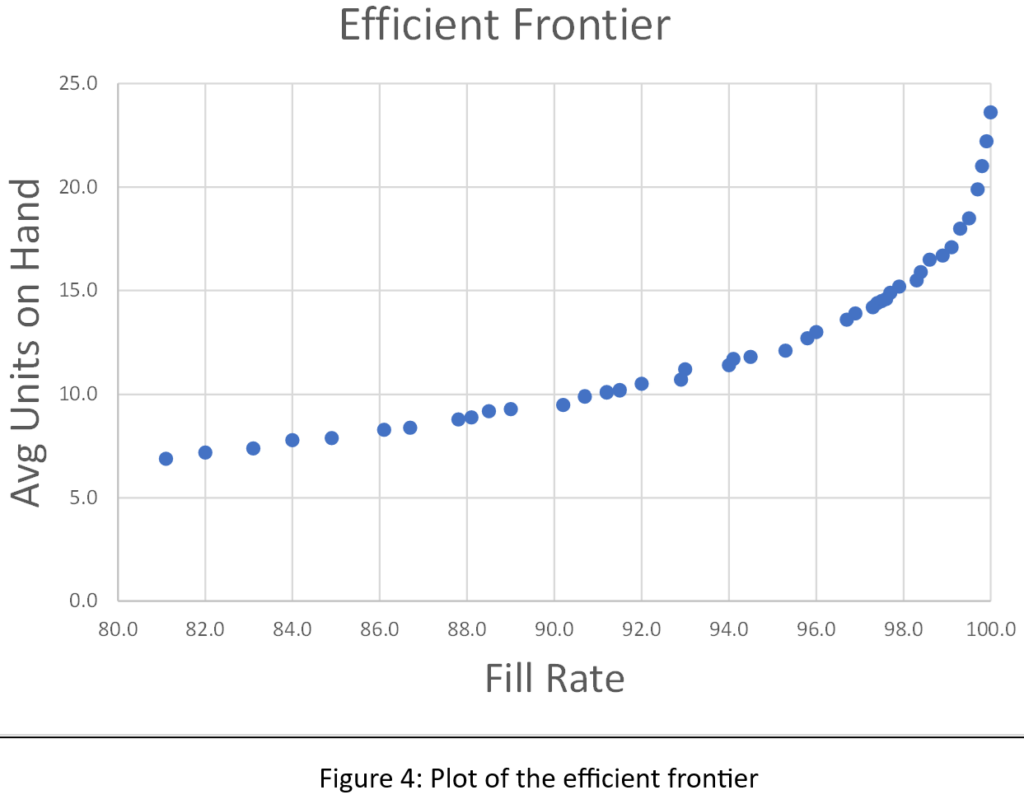

We sorted the results of all 1,085 simulations to identify what economists call the efficient frontier. The efficient frontier is the set of most efficient Min/Max pairs to exploit the tradeoff between fill rate and units on hand. That is, it is a list of Min/Max pairs that provide the least cost way to achieve any desired fill rate, not just 80%. Figure 4 shows the efficient frontier for this problem. Moving from left to right, you can read off the lowest price you would have to pay (as measured by average inventory size) to achieve any target fill rate. For example, to achieve a 90% fill rate, you would have to carry an average inventory of about 10 units.

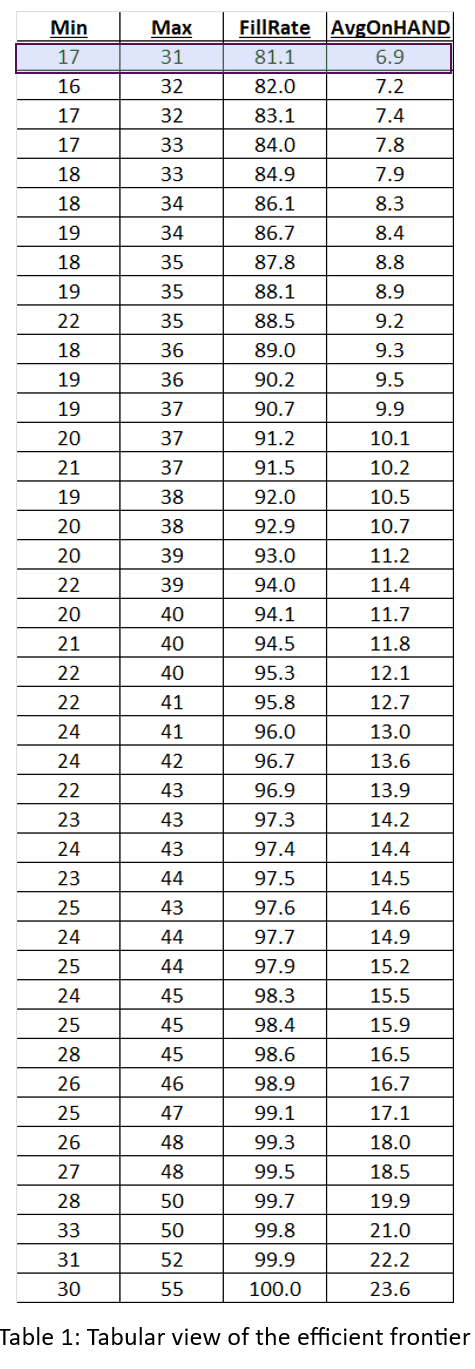

Figures 2, 3, and 4 show results for various Min/Max pairs but do not display the values of Min and Max behind each point. Table 1 displays all the simulation data: the values of Min, Max, average units on hand and fill rate. The answer to the guessing game is highlighted in the first line of the table: Min=7 and Max=131. Did you get the right answer, or something close2? Did you maybe get onto the efficient frontier?

Conclusions

Maybe you got lucky, or maybe you do indeed have a Golden Gut, but it’s more likely you didn’t get the right answer, and it’s even more likely you didn’t even try. Figuring out the right answer is extremely difficult without using the digital twin. Guessing is unprofessional.

One step up from guessing is “guess and see”, in which you implement your guess and then wait a while (months?) to see if you like the results. That tactic is at least “scientific”, but it is inefficient.

Now consider the effort to work out the best (Min,Max) pairs for thousands of items. At that scale, there is even less justification for playing the Inventory Guessing Game. The right answer is to play it… Smart3.

1 This answer has a bonus, in that it achieves a bit more than 80% fill rate at a lower average inventory size than the Min/Max combination that hit exactly 80%. In other words, (7,13) is on the efficient frontier.

2 Because these results come from a simulation instead of an exact mathematical equation, there is a certain margin of error associated with each estimated fill rate and inventory level. However, because the average results were based on 100 simulations each 365 days long, the margins of error are small. Across all experiments, the average standard errors in fill rate and mean inventory were, respectively, only 0.009% and 0.129 units.

3 In case you didn’t know this, one of the founders of Smart Software was … Charlie Smart.